Santiago (1585)

Filipe Castro, Paulo Jorge Rodrigues, and Chase Oswald

Country: French Indian Ocean

Place: Bassas da India

Coordinates: Lat. -21.515578; Long. 39.644197

Type: Nau

Identified: Yes

Dated: 1585 (Historical accounts)

Introduction

Santiago hit the atoll of Bassas da India at full speed during the night, on its way to India, in 1585.

As the flagship of a fleet that included the ships S. Lourenço, S. Salvador, S. Francisco, Santo Alberto and Reis Magos, Santiago left Lisbon on the first days of April of 1585, loaded with money, painted leather items, and merchandise to sell in India.

It was commanded by Captain Fernão de Mendonça and sailing with master Manuel Gonçalves, and pilots Gaspar Gonçalves and Miguel Rodrigo. In all it carried 12 pieces of artillery, consisting of two camelos, two esperas and eight berços, of which four were called falconetes, due to their large dimensions.

Santiago carried between 450 and 500 people, among whom were perhaps 200 sailors and 30 women and an undetermined number of children. Among the crew and passengers were eight priests, including Frei Tomás Pinto, appointed General Inquisitor in India.

Only three days out of Lisbon a storm separated Santiago from the fleet and it traveled to India without major incidents, other than encountering a caravel from Sesimbra, bound for the Canary Islands and persecuted by an English pirate, which abandoned the chase in view of the large ship. Aboard people tried to cope with the boredom with an impressive number of masses, processions, gamble, and gossip.

After passing the Cape of Good Hope the pilots focused on avoiding the Bassas da India atoll – sometimes also referred to as Baixo da Judia – but miscalculated its position and on August 19 hit these shallows at full speed, ramming the corals and embedding its lower hull in them. The ship is said to have lost its bottom against the coral reef, and parts of its upper works possibly floated away and came to rest over the coral reef on the southern part of the atoll.

The account of this shipwreck was published by Gomes de Brito – Relação do naufrágio da nau “Santiago” no ano de 1585, e itinerário da gente que dele se salvou, escrita por Manuel Godinho Cardoso, e agora novamente acrescentada com mais algumas notícias – and details the anguish and the tragic end of almost the entire crew and passengers.

Linschoten clames that Santiago‘s pilot Gaspar Gonçalves was arrested upon arrival in Portugal but absolved of all responsibility. he is said to have returned to Bassas da India to recover the money lost with Santiago – an amount estimated at around 400,000 cruzados – and almost losing his nau S. Tomé in the endeavor.

The wreck site was found in December 1977 by a sailor named Ernest Erich Klaar, traveling around the world with his wife and three kids on a Thai vessel he named Maria José. Having left Bangkok five years before, Mr. Klaar heard the story of the Santiago supposed treasure at Durban, South Africa, and decided to go look for it. He found the shipwreck site – undoubtedly already looted – without much difficulty and raised four small bronze guns, which he transported to Europe. In 1980 he returned to South Africa, charted a salvage vessel and sailed to the Santiago shipwreck site.

The artifacts recovered in 1980 included another eight bronze guns, an astrolabe, several kilos of scattered silver coins plus a large concretion also of silver coins, one gold coin, a copper cauldron, a broken crucifix, two religious medals, a gold bracelet, some silver objects, iron and lead artifacts, some intact ceramics, rolls of lead sheet and iron cannon balls.

The sale of the artifacts was organized in England and a company named Santiago Marketing was created in 1984 and tried to sell the bulk of the collection for $800,000. With no buyers interested, the Portuguese Museu de Marinha ended up buying eight of the guns and the astrolabe, and a number of other artifacts were bought by the South African Natal Museum.

Upon learning about the salvage of the Santiago shipwreck the French government sent an expedition to the atoll, but not much information was ever published from this survey. They reported heavy looting of the site.

Account

The account of the wreck of Santiago was authored by Manuel Godinho Cardoso and originally published in Lisbon in 1602. Godinho Cardoso was likely not a survivor of this wreck, but possibly had close knowledge of the shipwreck acquired from interviews and conversations with survivors. Godinho Cardoso most likely gathered this information while performing a series of official investigations into the disaster. In his account, Godinho Cardoso points out that it was impossible to determine responsibility for the incident as every officer blamed one another for Santiago’s loss. Godinho Cardoso bitterly describes the wreck of Santiago, often openly referring to the incompetence of Portuguese mariners (Duffy, 1955: 33). It should be noted that Godinho Cardoso’s account begins with the wrecking of Santiago, while the voyage details expanded upon by Gomes de Brito were extracted from an unknown text, concerning the voyage from Lisbon up until the wrecking (Duffy, 1955: 177).

Captained by Fernão de Mendonça and carrying many Jesuit missionaries and the new Inquisitor General of India, Frei Tomás Pinto, Santiago set out from Lisbon, bound for India on April 1st, 1585. Three days into the voyage Santiago encountered a severe storm and was nearly lost. While this near catastrophe early in the voyage convinced many onboard the Santiago to favor returning to port, the storm soon subsided and the ship resumed its course. Three days after the storm subsided, two unfamiliar sails emerged on the horizon. In response, Santiago’s crew hastily prepared the ship for battle. This effort was done with great difficulty as the decks had been over-encumbered with a great number of crates and casks. As fortune would have it, one of the ships turned out to be a Portuguese caravela, chased by an English ship. Upon sighting Santiago, the English ship swiftly halted its pursuit of the caravela and left the company of the Portuguese ships. Somewhere off the coast of Guinea, Santiago found herself becalmed for sixteen days, slowly drifting across the equator in a scorching heat by May 27th. Intermittent winds eventually prevailed and in two months Santiago rounded the Cape of Good Hope and began sailing north along the coast of Natal. Unfortunately, on August 5th, the winds began to die once more. Fearing that Santiago might be becalmed indefinitely if they were to attempt passage outside Madagascar towards Cochin, the decision was made to instead proceed directly north through the perilous Bassas da India shoals, at approximately 22° (Duffy, 1955: 115). If the winds changed and picked up before reaching the Bassas da India the Santiago would change course once again and sail directly to Cochin; however, if they continued their current course the plan was to make port at Mozambique for food and water, and from there sail to Goa (Duffy, 1955: 115-116).

The passengers carrying valuable cargo detested this plan and began a whisper campaign against it, as they feared that once the ship made port in Mozambique she would also be wintered there in which case they would incur a loss on the goods they wished to barter in India. By August 19th, Santiago continued north, approaching the shoals of Bassas da India. On this day the pilot measured the sun and calculated that the shoals approximately seven to eight leagues (38 to 44 km) to the north (Duffy, 1955: 116). That night the crew assumed they had already passed the shoals during the day when in fact, they were upon the shoals. Santiago struck three times and the bottom of the ship mounted the reefs (Duffy, 1955: 116-117). Two of the decks were instantly shattered to pieces, while another two decks were thrown, together with the masts and sails, onto the top of the shoals, with the mainmast breaking at the base upon impact. Santiago wrecked with more than 375 people on board (Duffy, 1955: 129). According to Cardoso’s account, in the ensuing chaos all those on board began to confess their sins en mass, forming a mob around the priests and filling the night air with their wails. In the light of the coming dawn, those aboard were able to gaze upon their predicament. The reef upon which they had dashed themselves was approximately twelve leagues (67 km) around and four leagues (22 km) across. At low tide it was covered in merely two to three hands of water (about 2 to 3 m); however, by high tide, there was no foothold to be found within three leagues (17 km) of the Santiago, aside from a group of large rocks that ran northward (Duffy, 1955: 117).

The red-colored coral was fragile but poisonous and razor-sharp, leaving bloody wounds whenever it touched human flesh (Duffy, 1955: 117-118). Santiago itself was fragmented into a rough triangle of floating remains consisting of the stern, bow, and one of the ship’s sides. In the middle of the triangle was a pool of water that was six feet (2 m) in depth at high tide, while on the north side there was a small opening through which the survivors eventually used rafts to escape. On August 20th, the captain and 24 others gathered in the only intact small boat and attempted to sail to safety on a supposed investigative expedition, promising to return forthwith for the remaining survivors who still clung to the remains of the ship. Father Tomás Pinto was to accompany them on this journey but was persuaded to stay aboard to offer spiritual guidance to the stranded passengers and crew. To the dismay of those still aboard, the boat never returned. In a panicked effort to save themselves, many aboard the Santiago mistakenly decided to enter the water or cling to floating hull remains, all of whom were swept away by the ensuing undertow and drowned. For two days those aboard the shipwreck were trapped with no way to safely leave the ship, until on the third day when heavy waves broke apart the ship’s side, releasing a damaged longboat. Galvanized by this momentary fortune, a group of survivors under the elected command of Duarte de Melo repaired the longboat with pieces of wood from crates, using torn portions of their shirts and Flemish cheese for caulking, hoping to escape in it as the tide returned (Duffy, 1955: 118).

The longboat was ill-equipped in provisions, carrying only several cases of marmalade, a few kegs of preserves, cheese, a flask holding six pints of orange flower water, and a barrel of wine. As for equipping the longboat, those on board were able to rescue a pike, an oar, and a sheet. Using the oar the crew constructed a makeshift mast, from the pike they made a yard, sewing the sheet together with bits of cloth they crafted a sail, and some fishing line became a stay and halyard (Theal, 1898: 343). After repairs on the longboat were complete Father Pinto came to inspect the boat, not wanting to be abandoned a second time, he compared the boat with one of the rafts being built and decided upon entrusting the former (Duffy, 1955: 118-119). Seeing Father Pinto favoring the longboat the other panicked survivors desperately swarmed the longboat and threatened to flood it with their weight. Duarte de Melo proposed to Father Pinto that he convince the mob to relieve themselves of their weapons. Out of respect for Father Pinto, many of the men respected his wishes and dropped their arms, allowing the longboat to be pushed off from the reef at high tide with no trouble from the hundreds of survivors being left behind (Duffy, 1955: 119). It should be noted, however, that before launch Duarte de Melo was approached by some of the sailors and the boatswain’s mate that their voyage could not commence until there were fewer people aboard the boat. Agreeing, Duarte de Melo sent forth five men with swords among the survivors and had seventeen of them thrown out into the sea, including men who had worked feverishly to repair the boat (Duffy, 1955: 120).

As the tide continued to rise the five rafts that had been constructed were launched with great difficulty, as those aboard were not only fighting against the reefs and waves but also defending themselves with swords against those still trapped onboard that tried to board them. Both men and women who attempted to cling to the sides of the rafts for safety were beaten off and wounded by those already on them. The reefs were quickly littered by the men and women who were refused entry aboard the boat or rafts, many of whom began to drown as the tide came in. Two women and a great number of men tried to swim after the boat and rafts, but all drowned in the attempt. One of the individuals, a boy of only fifteen, swam nearly half a league (3 km) in chase of the boat, upon reaching it he was met with a sword in his face, which he fearlessly grabbed on to as if a rope and refused to let go until they let him onboard (Duffy, 1955: 119). By that evening the rafts passed the highest portions of the reefs where many had sought refuge from the tide. Thinking they may have renewed attempts at salvation many of the survivors climbed down into the freezing water calling out to their friends and relatives in the crowded rafts, but their cries would go unanswered, silenced by the sea (Duffy, 1955: 120).

Initially, after exiting the reef those aboard the longboat were not able to find land, after much discussion, it was decided that they would continue with their voyage and not return to the ship (Theal, 1898: 342). Around this time those onboard created an additional foresail, using another oar as the mast, swords for the yard, and shirts for the sail. Additionally, because the seawater was sprayed over the sides of the longboat, the crew crafted screens from colored cloth retrieved from the reef; using planks taken from the deck they were also able to craft a rudimentary rudder. Using a mariner’s compass, the crew steered north by north-west. At this point they were extremely anxious to spot land as the longboat was taking on a vast deal of water as she was greatly exposed. The crew’s daily rations consisted of a portion of marmalade and three pints of wine, heavily mixed with the saltwater that continually washed into the longboat. For the first two days, they navigated through heavy seas, until on the third day, Wednesday, the weather calmed, and the wind shifted to the north-east, making the crew change course, steering north-west. As the currents eventually picked up, the crew dismasted the longboat and began rowing using the three oars. On the following Friday, the crew approached Sofala, signaled by whale sightings and shallow waters; however, they could not cast anchor as they only had a ten-fathom line (18 m) (Theal, 1898: 343). August 24th, the crew was able to anchor in nine-fathoms (16 m) of water at daybreak and as the morning fog dissipated, come midday, they finally sighted land, along with the smoke of native clearings (Theal, 1898: 343-344).

Suffering greatly from dehydration many aboard the longboat urged the rest to land immediately, but the experienced shipmaster amongst them encouraged the crew to continue along the coast until they reached the first islands near Mozambique. The master believed that not only would it be easier to reach Mozambique from that location, but he also believed that the longboat would go to pieces if they tried to land in their current position and he was wary of the natives. The crew followed the master’s advice and for three days they cruised along the coast until they reached three fathoms (5 m) of water in which they attempted to cast anchor. For this endeavor, the crew used a copper vessel filled with seawater as the anchor weight and a portion of untwisted rope serving as a cable. This makeshift anchor did not suffice. In response, the crew rowed all night keeping the prow of the longboat to sea as to not accidentally strike her against any rocks. During the four days that followed the longboat traveled against the wind for over 40 leagues (222 km). On the third day since the crew tried to anchor the sea became violent, with the wind running south-west and the waves becoming increasingly rough. The crew decided to run ashore, lest the longboat be overcome. Surrounded by rocks and at low tide with a crosswind, the crew steered the longboat towards land. Miraculously, despite the overpowering waves and spray that covered the longboat, the crew was able to safely land the craft and all the provisions within, whereupon they planned to beach the longboat for the night and set out for the islands near Mozambique after the sea had calmed and drinking water had been obtained (Theal, 1898: 344).

After landing, the crew investigated the interior of the land where they found ditches of water in which they used to fill up a barrel that was brought back to the longboat. Back at the beach, the crew came across a native who was willing to barter with them, trading some fish for one of their hats. Following this exchange, the Portuguese briefly sent one of their own back with the natives to their village to gather fuel. Upon their return, the Portuguese were given directions towards Quelimane, to the north-east, and Luabo, to the south-west. The following night as the Portuguese slept near the beach, the captain had laid within the chest that they had brought with them in the longboat, upon seeing this chest the natives forced themselves upon it, hoping to scrounge anything of value. Not long after, a second group of natives arrived on the scene, who after arguing with the first group plundered the longboat and surrounding area, taking swords from the beach and the sails made of cloth from the longboat. In the morning, the Portuguese left, setting off north towards Quelimane. Shortly into their trek, they were assaulted by more natives, who robbed them and stripped them naked. Portuguese who could not remove their articles quickly enough found themselves trampled in the frenzy (Theal, 1898: 345). From that instance on the Portuguese traveled up the coast weak and completely exposed (Theal, 1898: 346). Eventually, with the aid of friendly natives who were allies of the Portuguese crown, the survivors of the Santiago shipwreck were able to reach Luabo (Theal, 1898: 346-348). It was in this place that the survivors were warmly and hospitably welcomed by Francisco Brochado. Brochado was a former servant of the Infante Dom Luis who had spent the past 30 years as the chief warden of the river Cuama, overseeing that region’s trade with Sofala. At this time, only 18 survivors of the Santiago were left alive (Theal, 1898: 348). Eventually, by November 16th, most of the survivors in the company of Brochado left for the town of Sena, where the survivors arrived on November 25th (Theal, 1898: 349-353). By December 27th, the survivors left Sena for Quelimane, which they reached on January 10th. The survivors then left Quelimane for Mozambique, arriving safely on February 21st, 1586 (Theal, 1898 354).

Site

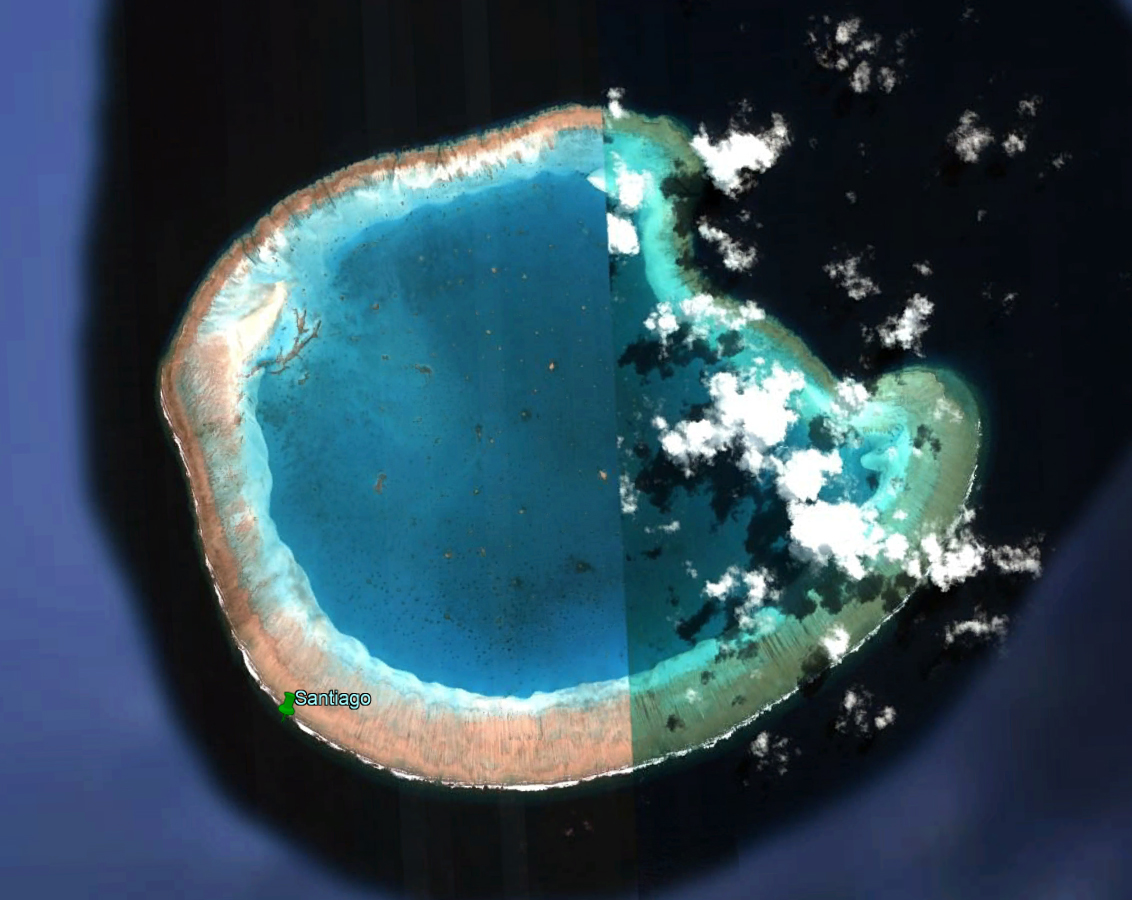

Located in the Mozambique Channel at lat. 25° 27 S., long. 39° 45 E., the Bassas da India atoll is part of a cluster of small French-controlled islands, the Iles Esparses (fig 28). At high tide the Bassas da India becomes submerged within the channel, leaving it uninhabitable. The atoll is submerged in one to three meters of water, and during low tide the enormous circular coral reef stretches between 10 to 12 kilometers in diameter. The flatter portion of the reef is at times over a kilometer wide above the water and at low tide it creates an enclosed lagoon populated by large vertical coral outcrops. The current is described as powerful and accompanied by hazardous whirlpools; a gap on the north-east side allows water to circulate between the ocean and the lagoon during mid-ebb tide to mid-flood tide. Access to the islands is restricted as they are considered “complete integral natural preserves”, acting as habitats for sea-turtle to lay their eggs. Discovered by Gaspar Gonsalves, the atoll is positioned in the center of a sailing route frequented since the early 16th century and is known for the many sunken ships in the area. Unfortunately, in 1976 the site was looted by South African divers and a great number of artifacts were subsequently sold off to a plethora of museums around the world, such as the Natal Museum in South Africa and the Lisbon Navy Museum in Portugal (Bouquet et al., 1990: 81-82; L’Hour et al., 1991: 175-176).

Survey

As originally pointed out by the authors of the Bassas da India site reports, the aforementioned looting coincided with a book published in 1978 by Peter Throckmorton, The Sea Remembers, in which Santiago is identified among the wrecks at the Bassas da India atoll as early as 1977 (Throckmorton, 1987: 170, as cited in Bouquet et al., 1990: 83; L’Hour et al., 1991: 180). In response to the looting at the Bassas da India atoll, the French Ministry of Culture in partnership with American financial sponsors surveyed the atoll in September and October of 1987. The survey was designed to divide the reef into zones and consisted of two separate methods, the first method entailed walking across portions of the atoll with the aid of metal detectors starting daily at low tide. The second survey method consisted of using magnetometer readings of the lagoon and included the use of two magnetometers which produced tens of kilometers of profiles in the center and western side of the lagoon. Surveys of the outer margins of the atoll quickly proved impractical, for the seabed reached depths as far as 300 to 400 meters deep around 200 meters from the atoll and nearly 2000 meters in depth about 1.6 kilometers away from the atoll. The southern portion of the atoll which measures 25 kilometers of the total 40-kilometer circumference is constantly barraged by deadly waves between three and seven meters in height. While a survey of the northern sector of the atoll proved relatively easy it was the hazardous southern sector that visibly proved most difficult for it was brimming with nearly flooded fissures created by the endless currents and collapsing dead coral. During the survey of the treacherous southern sector, several historical and modern shipwrecks were analyzed, including one tentatively identified as the remains of Santiago from 1585 (Bouquet et al., 1990: 82-83; L’Hour et al., 1991: 176 -180).

Finds

Described as a “relatively homogeneous site”, the artifacts are clustered in a ten-meter-wide and 30-meter-long basin, containing 10 cast-iron cannons and two large iron anchors. Five additional anchors and a large gun encased in coral lay within a 50-meter radius of the artifact cluster, all of which appear to be European and from the late 16th century. Based on historical documentation and their 16th century characteristics the cannons and anchors were tentatively linked to the Santiago. Despite the possibility of additional artifacts potentially buried under one meter of dead coral, further excavations were not carried out at the tentative Santiago site for fear of jeopardizing the lives of the divers due to the hazardous conditions of the area. Unfortunately, a lack of adequate archaeological evidence and dangerous conditions hampered investigations and has prevented a definitive identification of the site (Bouquet et al., 1990: 83; L’Hour et al., 1991: 179 -180)

Anchors

Two anchors are described in the basin carved by the ship when it rammed the reef and another five scattered in an area 50 m around the site.

Guns

In a newsletter sent out by The Cannon Association of South Africa dated September 2006, twelve bronze Portuguese cannons were analyzed and described at the request of the Centre for Portuguese Nautical Studies (SA). Of these twelve, four were housed in the Natal Museum of South Africa and eight were stored on wooden planks in a building near an anonymous municipal establishment. Four of the guns were said to have originated from the São Bento while the other eight were supposedly salvaged from the Santiago site, all of which display the Portuguese crest and armillary sphere (de Vries, 2006: 1). The purported Santiago guns will be described below as they organized within the newsletter.

Durr 694 ex Santiago: Chambered perrier or stone firing cannon with “camelo” proportions. Notably, the first reinforce is smaller in diameter than the second, possibly reducing the weight and amount of bronze used. This gun is also missing all four lifting rings. Guns of this type typically measured between eight to 14 calibers in length (de Vries, 2006: 1).

Durr 695 ex Santiago: Culverin or “colubrina”, this gun is described as being long in proportion to its caliber, being 27 calibers in length. The author doubts that this gun was chambered (de Vries, 2006: 1).

Durr 696 ex Santiago: Culverin or “colubrina”, nearly identical to Durr 695, measuring 27 calibers in length. Besides the Portuguese crest and armillary sphere, this gun displays the mark of King Sebastian 1557-1578, via the phrase “SEBAS TANIVS”, displayed below an “R” and above an “I” (de Vries, 2006: 1).

Durr 876 ex Santiago: “Berço”, a swivel-gun with a 72 mm bore, containing a separate iron chamber, although the chamber was not recovered from the wreck site, most likely having corroded away. In addition to the Portuguese crest and armillary sphere, this gun contains a founder’s mark containing a single letter “C” on the chase. The receiver which held the chamber is asymmetrical, the left wall measures 45 mm in thickness, while the right wall measures 58 mm in thickness. The author suggests that due to a lack of corrosion on the cavity the gun was probably cast in this manner, most likely accidentally (de Vries, 2006: 1).

Durr 878 ex Santiago: “Pedreiro” or stone firing gun, of 173 mm and 16.3 calibers in length. The first reinforce was of greater diameter than the second and showed no signs of whether or not it was chambered. According to the author guns of the caliber and proportions were referred to as “camelete”. The cannon is marked as weighing 12-2-14. In addition to the Portuguese crest and armillary sphere, the gun is marked with the letters “S B T A”, potentially referencing King Sebastião (de Vries, 2006: 1).

Durr 879 ex Santiago: “Berço”, a swivel-gun with a 108 mm bore containing a separate iron chamber which likely measured 550 mm in length. At the top of the rear end of the receiver, the gun has the weight measurements 7-2-2, carved into it. Besides the Portuguese crest and armillary sphere, the gun contains the partially discernable mark of “SEBAS TANVIS” (de Vries, 2006: 2).

Durr 882 ex Santiago: “pedreiro” or “camelete”, with a bore measuring 179 mm and chambered to 129 mm in length. Notably, the lifting rings on this gun are misaligned. Besides the Portuguese crest and armillary sphere, all of which are in excellent condition this gun also contains the mark of “FCRo”, similar to the founder’s marks belonging to some of the São Bento cannons (de Vries, 2006: 2).

Durr 883 ex Santiago: “pedreiro” or “camelete”, with a bore of 180 mm. The weight is etched into the top of the base ring, reading 12-3-13. The author notes the caliber to bore ratio as 13.5. Besides the Portuguese crest and armillary sphere, the gun contains the partial mark of “SEBAS TANIVS”, however according to the author only the last two letters of each word are still legible (de Vries, 2006: 2).

Iron Concretions

Not reported.

Hull remains

Not reported.

Caulking

Not reported.

Fasteners

Not reported.

Size and scantlings

Hull remains not reported.

Wood

No timbers were reported.

Reconstruction

Beam: 16.5 m

Keel Length: 33 m

Length Overall: Estimated 50 m

Number of Masts: Almost certainly 3.

Tonnage: 900 tons.

References

Bousquet, G., L’Hour, M., and Richez, F., “The discovery of an English East Indiaman at Bassas da India, a french atoll in the Indian Ocean: the Sussex (1738),” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (1900) 19.1: 81-85.

Brito, Bernardo Gomes de, História Trágico-Marítima, 2 volumes, Lisboa, Coleção Livros de Bolso nº. 278, Publicações Europa-América.

Linschoten, J. Huyghen van – The Voyage of John Huyghen van Linschoten to the East Indies, Book 1, Volume 1, p. 176-180, London 1663, The Hakluyt Society of London.

Quintela, vice-almirante Ignácio da Costa, Annaes da Marinha Portuguesa, nº.18-19, Lisboa, Colecções Documentos, Ministério da Marinha, 1975.

Reis, António Estácio dos, Astrolábios Portugueses adquiridos em leilão na Christie’s, Oceanos, Nº2, Outubro de 1989, Lisboa, Comissão Nacional para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses.

Santos, Nuno Valdez dos, A Artilharia Naval e os canhões do Galeão Santiago, Lisboa, Academia da Marinha, 1986.

Stuckemberg, Brian, Recent Studies of Historic Portuguese Shipwrecks in South Africa, Comunicação apresentada na Academia de Marinha em Junho de 1985, Lisboa, Academia de Marinha, 1986.