Saveiros da Bahia

Filipe Castro, Denise Gomes Dias, Rodrigo Torres, Samila Ferreira, Marcelo Bastos

Links: Academia: Saveiros da Baía;

Links: Marcelo Bastos’ Work.

I cultivate rhythms. That’s how it is. My head is like a museum. But the difference is that rhythms don’t become statues. They pass by you over and over. They come and live inside me, then go and live inside others. In other heads and thoughts.

Carlinhos Brown: World Music Portraits, Video Documentary 2004.

Introduction

Ships have been conceived following rules and recipes since times immemorial. To repeat a good shape has always been important for shipwrights, and the use of graminhos is just one of many strategies used by carpenters building boats and ships.

The algorithmic nature of certain recipes known to us attests to the sophistication and understanding required to conceive, build, and operate ships and boats, and its study constitutes a passionate field of research. Ships and boats have so many symbolic values, nested in so many semiotic systems, that the study of their conception and construction processes cannot be separated from the environment’s tastes, preferences, beliefs, and are part of a waterfront culture whose study has inspired many anthropologists, sociologists, writers, and poets.

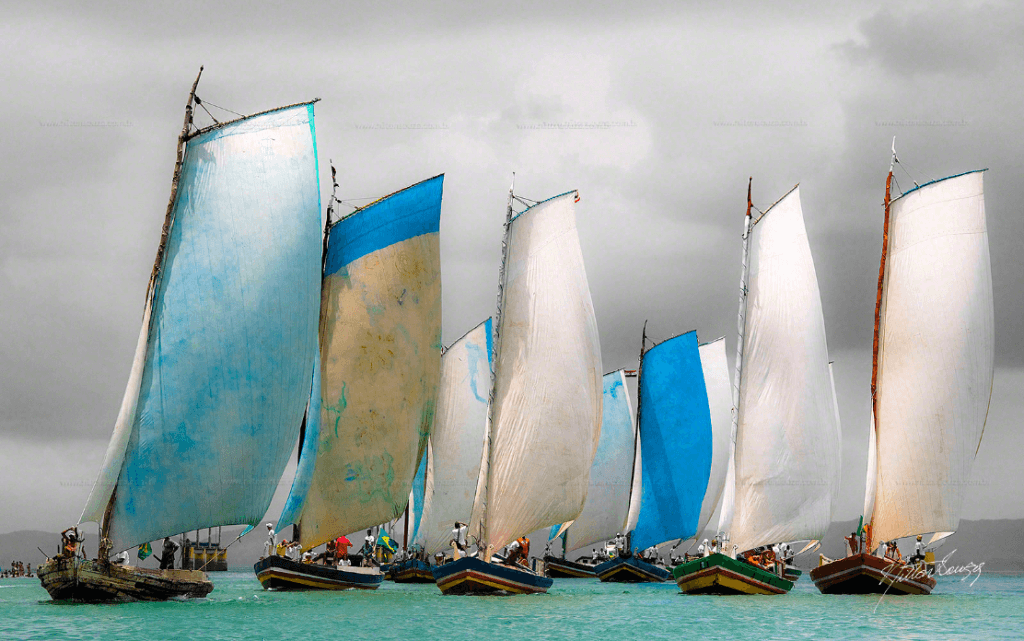

Few people are immune to the sight of a well-balanced vessel sailing fast through any body of water. The feelings of balance and harmonious relation with the environment for which they were built are often combined with the beauty of their colors and elegance of their rigging. In the case of the saveiros, their image is inseparable of that of the magic and sometimes breathtakingly beauty of the landscapes they inhabit.

This amazing shipbuilding culture was first published in the 1980s by John Patrick Sarsfield, in a series of tremendously important papers that detailed their methods and traditional knowledge. Sarsfield died tragically in Brazil, in a car crash on the way to pick up timber for the construction of vessels.

A fortuitous encounter, three decades later, of Filipe Castro and Denise Gomes Dias made it possible to relaunch this project and gather the wide interest that these vessels still gather in Brazil.

The project (re)started in December of 2013, when one of the authors visited Valença – invited by Denise Gomes Dias – and interviewed a group of shipwrights in order to assess the vitality of this persisting tradition, and decide whether it was worth studying this community. The report of this trip was published in the IJNA, in 2015, and this section repeats most of the points made then., and aims at adding more information.

In 2013, at Valença, we interviewed mestres Walter ‘Waltinho’ Assis de Santana, Francisco ‘Chico’ de Assis, Edir, Valmiro, Zuza, Tenório, and José ‘Zé Crente’ do Nascimento, and we paid a short visit to mestre Elpídio in Camamu, a nearby village. What we saw was a rich cultural environment where construction methods are handled from one generation to the next, evolve in the light of new tastes, market trends, shortage of old materials and availability of new ones, and cross-pollinates between villages, islands or shipyards.

The use of graminhos (mezzalune) to obtain a fair shape of the ships’ bottoms is only one of the secrets of the trade, and we decided to return and study the similarities and differences between these methods, the transfer of knowledge process, and the ways in which innovation has occurred.

While in some places, such as Valença, shipwrights seem to be struggling, in other places their activity is thriving. The business models in themselves were one object of our attention. In some places the ships are built at the shipwrights’ expense and sold afterwards, in other places the buyer pays for the work and the timber, and in other places a contract is established based on a project. Engineers are inevitable in the process of legalizing the larger vessels, but we were left with the idea that their role in the design and construction is not central.

The Saveiros of Baía de Todos os Santos

Swift, agile, elegant with their bright sails and colorful hulls, the saveiros were the workhorses that supplied Baía de Todos os Santos and distributed its manufactured goods throughout the cities and villages that surrounded that industrial center. Sugar, manioc, pottery, coconuts, palm oil and spices were transported raw and processed, to and from the city of S. Salvador, since times long forgotten (Dias 2009).

Anthropologist Pedro Agostinho (1973) made the case for its evolution from the colonial caravels through “the slower rhythm of cultural change, [which] may have preserved until today many archaic structures, forms and techniques.” His seminal work was later reedited with a set of magnificent images and established a history and a typology of these vessels (2011).

But international attention was primarily drawn to these vessels by John Patrick Sarsfield, who in the 1980s traced a hypothetical developmental line, which explained the introduction of the present gaff sails through Dutch influence and the change of name from caravela (or caravelão) to saveiro (Sarsfield 1985a). Furthermore, Sarsfield documented and published the construction method used by one of these Brazilian shipwrights, mestre (master shipwright) Walter Assis de Santana (Sarsfield 1985a, 1985b and 1988), and eventually raised funds to build a “caravel” in Valença (Carrell and Keith 1992; Nance 1992; Barker 1993; Macaulay 1993).

In 1996, a book by Lev Smarcevski presented a series of rules to build a 20 m long saveiro, used by local (master) shipwright, mestre João Bezerra, based on a graminho, which in the case described also contains the boat’s main scantlings (Smarcevski 1996). His book gathered the comments and explanations of mestreBezerra in the way the author understood them.

Although the two saveiros described by Sarsfield and Smarcevski are different – Sarsfield’s has a stern panel, while Smarcevski’s is double ended and has a roof (tijupá) – what they have in common is the use of molds, scales, and ribbands similar to those described in late 16th and early 17th century Portuguese documents to mark out the shape of their frames. The steps within the conception process and the vocabulary used in Valença and the Baía area suggest that these methods were imported from Portugal although it is not possible, at least at this point of our project, to point out when and how this knowledge was passed to shipwrights across the Ocean.

Examples

Saveiro from mestre Walter ‘Waltinho’ Assis de Santana

Saveiro from mestre João Bezerra

Shaping the Hulls

Step by step procedures (algorithms) for the determination of the basic dimensions and shape of a vessel were frequently used by shipwrights. A particular type of these methods by which shipwrights obtain the shape of a portion of the frames from a small set of molds, gauges and ribbands similar to the English whole-molding methodis well-documented throughout the Mediterranean, from the late Middle Age to the present, and can be found in historical documents along most of the northern coast of the Mediterranean, in the Iberian Peninsula, and in the Spanish New World (Palacio 1587). The use of these methods is suggested in French texts dating to the early 14th century (Sosson 1962; Rieth 2004) and described in Italian texts from the mid-15th century onwards (e.g. Jal 1840; Anderson 1925 and 1945; Lane 1934; Sarsfield 1984; Rieth 1996; Damianidis 1998; McManamon 2001; Bondioli 2003; Castro 2007). The influence of Italian shipwrights in Spain and Portugal is documented (Filgueiras 1989; Ciciliot 2000; Barker 2001) and several Iberian documents from the late 16th and early 17th centuries describe the use of molds, scales, and ribbands to build ships and boats (Barata 1989; Castro 2007; Olaberria and Olaizola 2013).

Shipwrecks containing evidence which suggests the use of molds, gauges, and ribbands, have been documented in Spain, Portugal, Canada, the USA, and Bulgaria. At least seven shipwrecks studied and published show evidence suggesting the use of these construction methods: in Spain the early 14th century Culip VI shipwreck (Prieto and Raurich 1989); in Portugal the mid-15th century Aveiro A shipwreck (Alves et al. 2001), the early 16th century Cais do Sodré shipwreck (Castro et al. 2011), and the early 17th century Portuguese Indiaman Nossa Senhora dos Mártires (Castro 2005); in Canada the mid-16th century Basque whaler San Juan (Loewen 1994 and 1998); in the USA the early 18th century Brown’s Ferry vessel (Hocker 1991 and 1992); and in Bulgaria the early 19th century Kitten shipwreck (Batchvarov 2009, 2014).

The Brown’s Ferry shipwreck is particularly interesting because it was found in the New World, in Georgia, USA, documenting the diffusion of these ideas across the Atlantic and into Anglo-Saxon America in the early 18th century. Perhaps less perplexing was the observation of molds, scales, and ribbands techniques in Brazil, in the 1980s. Described by John Patrick Sarsfield and Lev Smarcevski, Mediterranean whole-molding techniques are still widely used in the region of S. Salvador da Bahia for the design of the hulls of several types of working and leisure watercraft, some of which having overall lengths nearing 30 m. Sarsfield and Smarcevski’s accounts on the building of saveiros in the Bahia region are detailed and accurate, and document two variants of a method that is already explained in late 16th century Portuguese documents (Sarsfield 1985a, 1985b, 1991; Smarcevski 1996).

Transfer of Knowledge

Italian scholar Piero Dell’Amico proposed a model for the transfer of knowledge process, which states that shipwrights learn how to build ships in ways that can be clustered around three main situations: by oral tradition, practicing with an experienced master during a long apprenticeship; by oral tradition, practicing with an experienced master, but using partially geometric methods that may be poorly understood but are fixed and almost unchanged through time; and by using technical drawings and theories that can be learned in school and applied to wide ranges of watercraft, dispensing with the long empirical master-apprentice training (Dell’Amico 2002).

Another relevant contribution to this study was proposed by Ole Crumlin-Pedersen and Eric Rieth, who defined the concept of “architectural signatures” to trace the diffusion of technology and refine taxonomic analysis of ships and boats. “Architectural signatures” are particular construction traits that are described and analyzed in relation to their spatial and temporal distributions, and related to patterns of transference of knowledge within a particular cultural horizon (Crumlin-Pedersen 1991, Rieth 1998). In this context, the meme concept becomes particularly helpful to analyze spatial and temporal distributions of construction features, and try to understand where knowledge resides and how it travels in the shipbuilding world. Considering a meme as an idea, a belief, a ritual, a gesture, or any pattern of behavior, a vessel can be described as a population of memes, or “units of culture,” and we can try to understand how these ideas and solutions are transmitted and adapted, in order to survive (Dawkins 1976). The development of watercraft can then be partially explained through a model similar to a Darwinian evolutionary model, providing we understand that the processes of mutation are not random and non-directional.

It is not obvious what knowledge is central and what is accessory in a building tradition nor, for that matter, what defines a particular type of boat. One of the shipwrights we interviewed told us that he decided to build “boats” but he did not know how the frames were fashioned with two moulds and one reduction scale. He asked his sister’s boyfriend, who was an apprentice with one of the best mestres in the region, to teach him how to design the graminho and apply it to the bottom molds, for which he bought him a case of beer. With that knowledge he sketched a boat on the beach sand, “understood the whole process,” and built a small vessel, which he called Vai-se Ver (We Will See), sold it, and started his business with that money.

To understand how and when the shipwrights of this region started using molds, scales, and ribbands to build ships and boats, the authors have planned a series of visits and interviews, and an archival investigation, namely into the genealogy of some of the known shipwright families. The main goal of this project is to try to understand the common traits in the shipbuilding methods observed in the region, and to try to trace their origin and transfer process. The present paper is intended as an introduction to this subject, and pertains to the methods described by John Patrick Sarsfield and Lev Smarcevski, compared with the observations made by two of the authors in a visit to the field in December 2013.

Timber

The acquisition of suitable timber also appeared to be an interesting subject as the entire shipbuilding activity is rather unregulated, while the tragic destruction of the Atlantic forest of the last century generated a highly regulated timber market. After our short visit we felt that all these subjects call for further research, and this paper is intended as an introduction to the subject.

Partially Geometric Methods

According to Dell’Amico the use of molds, scales, and ribbands requires a certain period of apprenticeship to understand the use of geometric aids, which can be used without a full understanding of the geometric steps needed to design the molds, calculate the gauges, or determine the number of pre-designed frames. In Valença the authors have observed several cases in which the shipwrights used the molds and the scales correctly, together with a number of rules of thumb passed onto them through oral tradition, without a full understanding of the entire design process.

As mentioned above, this process consists of the utilization of a small number of molds, gauges, and ribbands, to obtain – or repeat – a particular shape of a ship’s hull with reasonable accuracy. Before the development of lines drawings and lofting methods, the ability to repeat a particular hull shape was paramount to ship owners and shipwrights. To build “by eye” did not provide any guarantee of precision, even when the most skilled shipwrights available were involved.

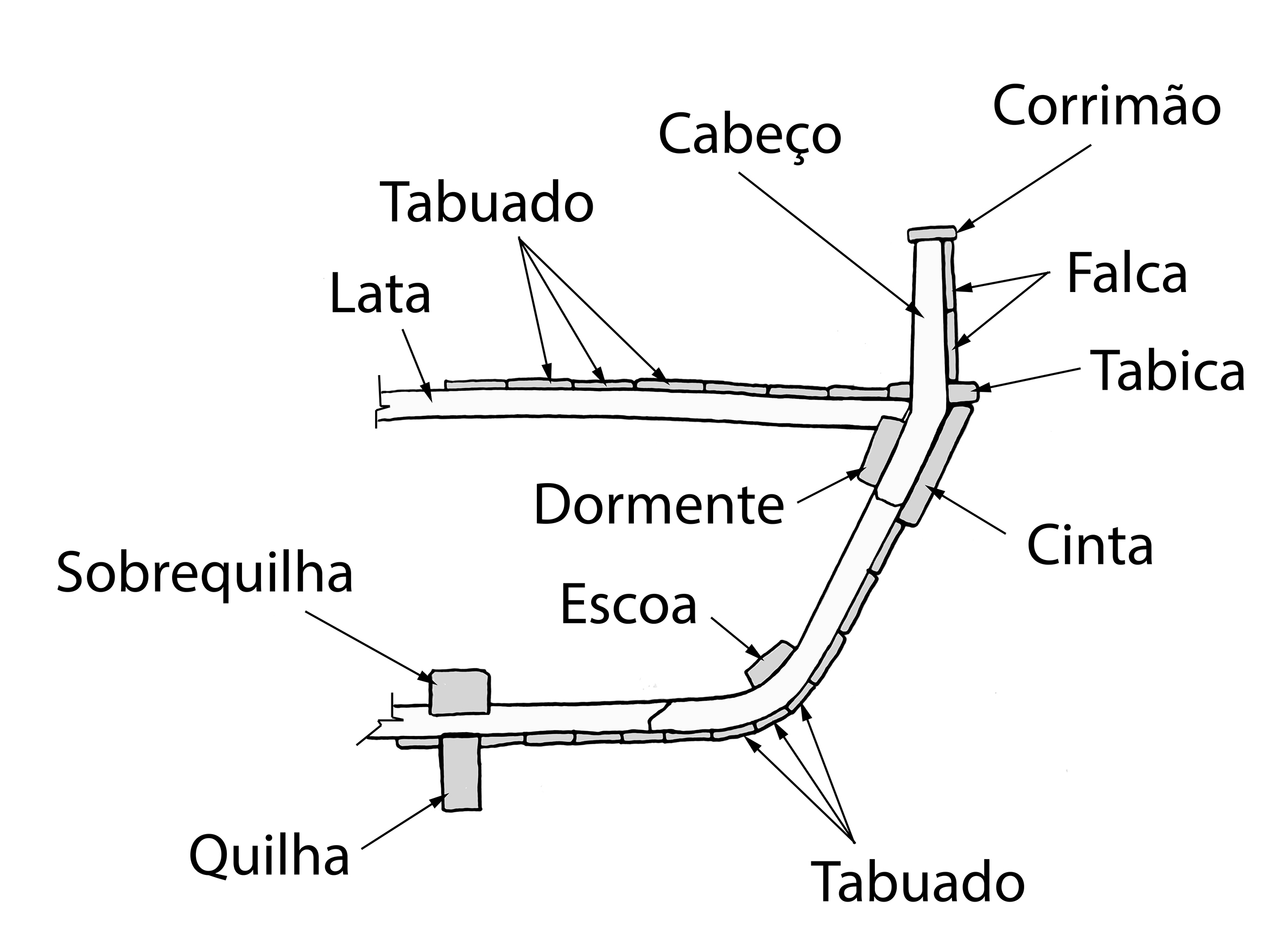

In the Iberian peninsula as in the Mediterranean, this system defines the shape of a hull from three basic longitudinal lines: the first outlines the shape of the keel and posts, the second is referred to as the turn-of-the-bilge line and defines the boundary between the vessel’s bottom and its sides, and the third is the main wale line or, in smaller vessels, the caprail line.

These three lines are defined in advance in the mind of the shipwright and materialized on the stocks through a non-graphic process, generally based on the use of a floor timber mold, a first futtock mold, and one or two gauges (in Portuguese graminhos), which allowed the shipwright to change the shape of each frame by sliding the molds according to a set of pre-established increments. There were no construction drawings used.

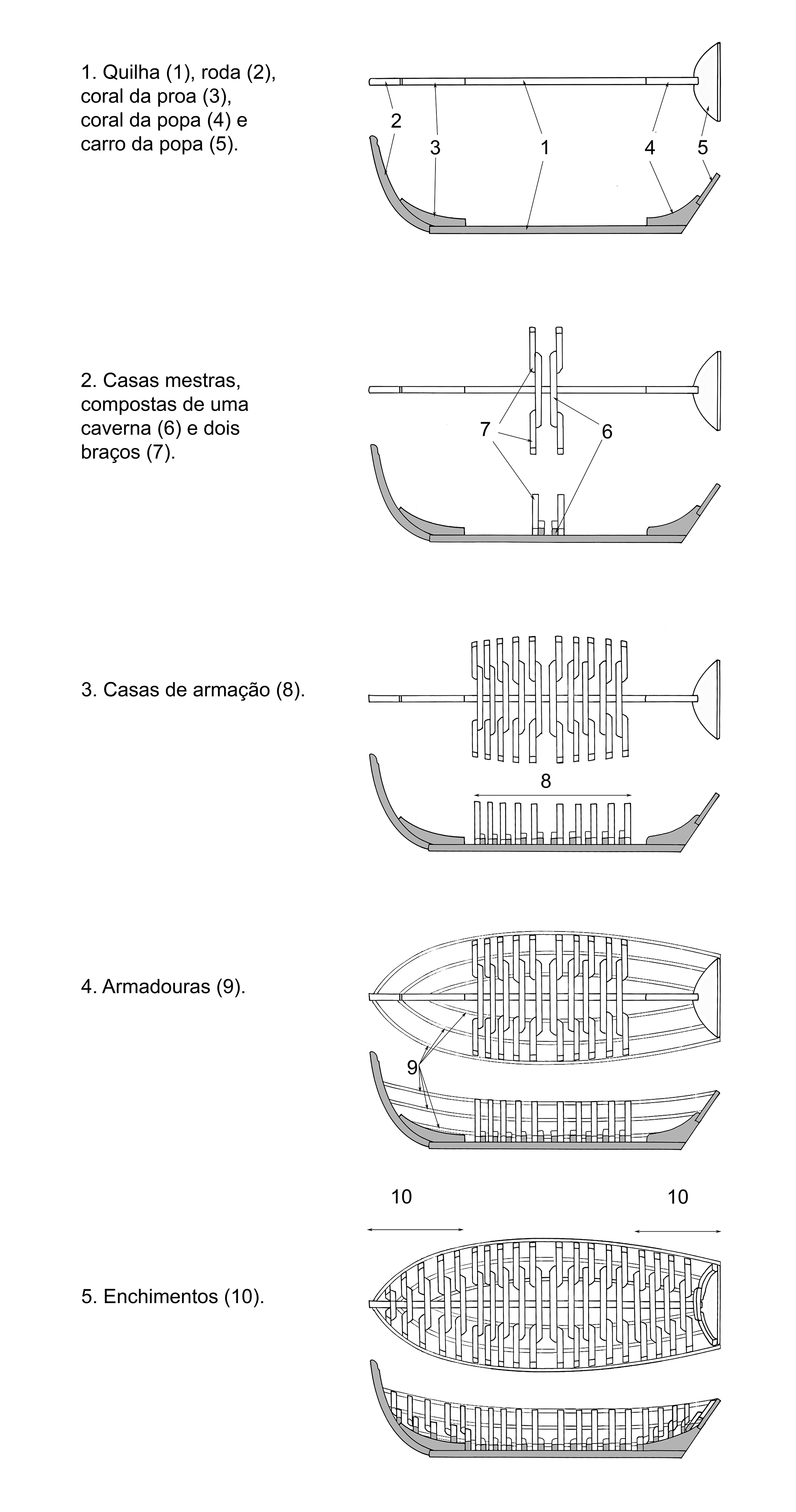

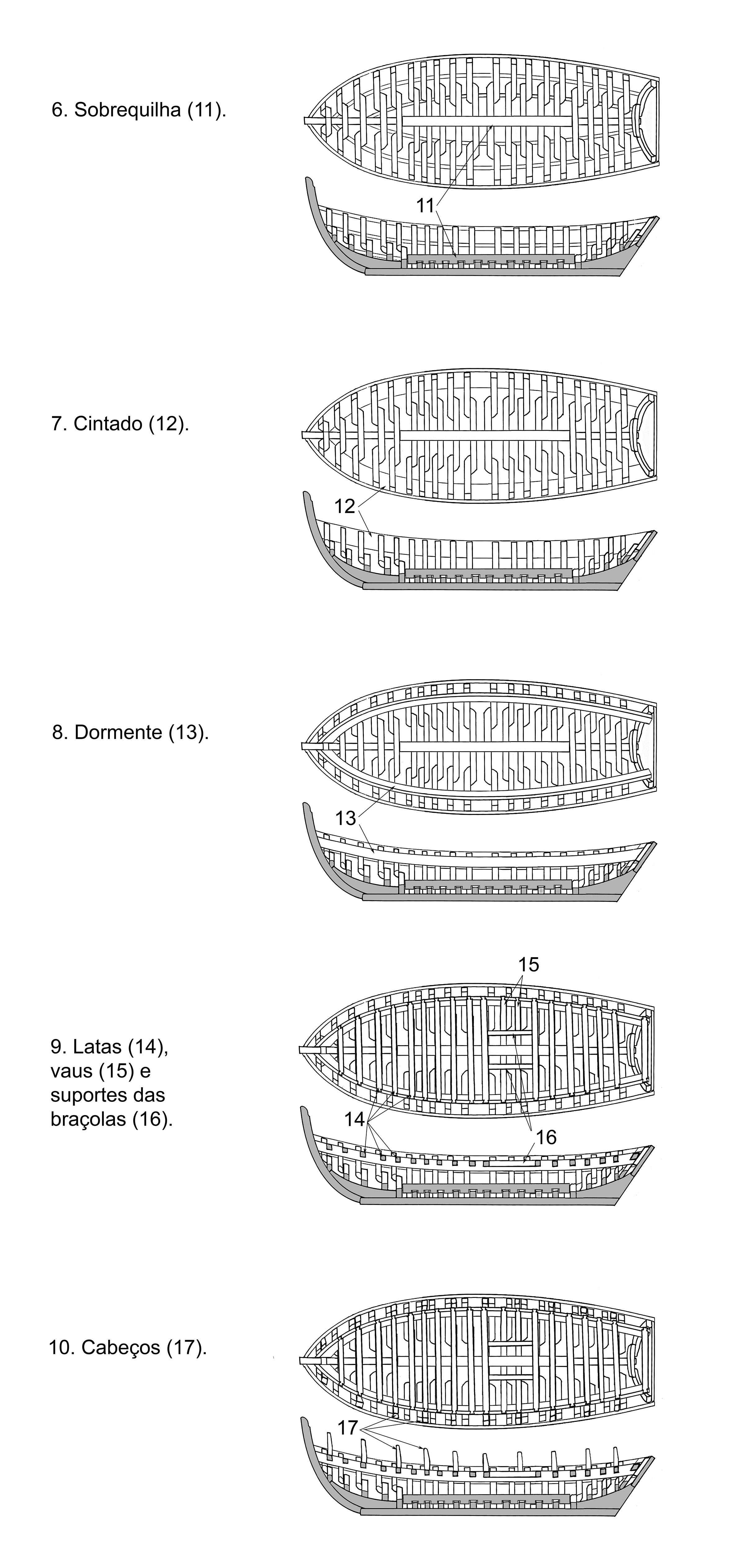

After mounting the keel and erecting the stem, sometimes a bow knee (coral da proa), a stern knee (coral da popa), and sternpost on the stocks, the shipwrights assembled the master frame – or a pair of master frames, as it is usual in Valença – using two floor timbers and four futtocks whose shape was defined by the respective molds. After about 1500, a stern panel was sometimes mounted on the stern, by adding the fashion pieces and a number of transoms between these. In the saveiros this stern panel is made of thick boards horizontally laid, and stands on the stern knee, against which the sternpost was laid, with a tenon which rested on a mortise carved on the upper surface of the keel.

After mounting this pre-assembled master frame on the keel, the shipwrights cut and assembled a certain number of pre-designed frames from the same molds, made increasingly narrower as their position on the keel moved away from the master frame. In other words, although the shape of these frames was basically the same as the master frame’s, as they were positioned further away from the master frame, each frame’s bottom was narrowed (and sometimes raised) a bit more than the previous one. In this way the turn of the bilge point of each frame was raised and narrowed towards the ends of the vessel, giving the hull a fair shape.

Once these pre-designed frames were mounted and levelled on the keel, a number of ribbands (in Portuguese armadouras) were nailed to the frames and posts, defining the hull shape. The remaining frames were fashioned from these ribbands. According to the shipwright’s taste and will, the pre-designed frames could be contiguous and form the central portion of the hull, as in the Pepper Wreck (Castro 2005, 147-179) or the San Juan cases, or could be placed at certain intervals, as in the Brown’s Ferry shipwreck (Hocker 1992, 13).

After the remaining frames were attached to the keel and perfectly levelled, a keelson would be placed over them, often notched to fit their upper portions, and bolted to the keel. After this, the hull could be reinforced with wales and stringers, the lower deck beams laid, and the hull planking started.

There are countless ways of building a vessel with molds, graminhos, and ribbands, and the authors have documented several variations in early modern as well as recent texts, in the archaeological record, and now in the Baía de Todos os Santos area. In this paper we will present the methods of mestres Walter Santana and João Bezerra, as described by Sarsfield and Smarcevski, which are intended to establish a basis for a broader understanding of these methods and their probable origins, and relate a number of common practices presently in use.

Bahia 2013

In December of 2013 Denise Gomes Dias and Filipe Castro visited Valença and interviewed a group of shipwrights in order to assess the vitality of this persisting tradition and decide whether it was worth further study. As mentioned above, at Valença we interviewed mestres Walter ‘Waltinho’ Assis de Santana, Francisco ‘Chico’ de Assis, Edir, Valmiro, Zuza, Tenório, and José ‘Zé Crente’ do Nascimento and we paid a short visit to mestre Elpídio in Camamu, a nearby village. What we saw was a rich cultural environment where construction methods are handled from one generation to the next, evolve in the light of new tastes, market trends, shortage of old materials and availability of new ones, and cross-pollinate between villages, islands or shipyards.

The use of graminhos (invariably mezzelune) to obtain a fair shape of the ships’ bottoms is only one of the secrets of the trade, and we decided to return and study the similarities and differences between these methods, the transfer of knowledge process, and the ways in which innovation has occurred.

The use of graminhos (invariably mezzelune) to obtain a fair shape of the ships’ bottoms is only one of the secrets of the trade, and we decided to return and study the similarities and differences between these methods, the transfer of knowledge process, and the ways in which innovation has occurred.

While in some places, such as Valença, many shipwrights seem to be struggling, in other places their activity is thriving. The business models in themselves were one object of our attention. In some places the ships are built at the shipwrights’ expense and sold afterwards, in other places the buyer pays for the work and the timber, and in other places a contract is established based on a project. Engineers are inevitable in the process of legalizing the larger vessels, but we were left with the idea that their role in the design and construction is not central. The acquisition of suitable timber also appeared to be an interesting subject as the entire shipbuilding activity is rather unregulated, while the tragic destruction of the Atlantic forest of the last century generated a highly regulated timber market.

All shipwrights interviewed during our 2013 visit to Valença were extremely helpful and clear in their explanations. Mestres Zé Crente and Chico were particularly patient and we ended up spending more time with them while we were in Valença. According to the interviewed, most ships are built for clients, and paid in several instalments. The compass timber is chosen by the shipwright, who goes with the timber supplier to the forest and marks the trees with chalk, using only the futtock mold and a metric tape.

Before the depletion of the Atlantic forest, high quality timber would ensure a longevity of 50 to 80 years for dugout canoes, boats and ships. Vinhático, a designation that refers several tree species (generally Plathymenia reticulata) was the preferred timber, followed perhaps by jataí-peba (generally Dialium guianense), both endemic. Today most saveiros are built with jack tree, an intrusive large fruit tree, known as jaqueira in Brazil (Artocarpus heterophyllus), whose branches “can supply all the curves for a boat” as mestre Chico put it.

Timbers were traditionally felled and the logs converted in the forest with axes – a task named farquejar or falquejar. Today timber suppliers and shipbuilders use chainsaws. We were amazed with the precision with which they cut the smallest details such as scarves, into the timbers, and we even witnessed them using a chainsaw to smooth the planks’ surfaces, instead of the traditional adzes. Planking and other straight timbers can be purchased directly from the timber suppliers.

All shipwrights seemed to follow similar rules of proportion in the design of these boats. The maximum beam is about one third of the length on deck, the depth in hold about one third of the maximum beam, and the transom two thirds of that measurement. This rule is not always followed, however, and a lot is left to both the shipbuilder and the future ship’s owner when it comes to define the main proportions of a saveiro. In Valença the flat of the floor amidships does not seem to be defined by any proportion, resulting from the shapes of the turn of the bilge and futtock arcs, which are cut from the molds, after setting the exact measurements of the depth of hold and maximum beam.

The scantlings are heavy and the craftsmanship good. A 10 m saveiro under construction at mestre Valmiro’s shipyard, in Valença, had eight predesigned frames (two central frames with no deadrise), a keel 9 cm sided and 21 cm molded, floors and futtocks 9.5 cm sided and 11 cm molded, deck beams 8 cm sided and 10 cm molded, and planking 3.5 cm thick.

The municipality expropriated a number of shipyards about a decade ago, to make a river walk, and today many shipwrights build their boats on the river margins and keep the tools in improvised sheds nearby. The keels are laid on blocks of wood or stone, and access to its lower face is achieved by excavating, when that is necessary. The stem and stern panels are shored, and so are some the frames.

With the exception of mestre Waltinho, all shipwrights interviewed established the ship’s scantlings and the number of pre-designed frames in relation to the length on deck, and determined the keel length after tracing the stem post and the stern knee (coral), which set the rake of the sternpost. All other shipwrights interviewed, however, mentioned simple rules of thumb. According to mestre Zé Crente, “a 9 m long saveiro takes eight predesigned frames (casas de armação), and one of 10 m requires 10 predesigned frames.”

The shapes of the stem post and stern knee are set by eye, according to the taste of the shipwright. The turn of the bilge and futtock arcs are also shaped by eye and are never circular arcs. The stern panel, assembled with thick planks, is normally half as wide as the maximum beam and shaped with the futtock arcs inversed (with the turn of the bilge up).

The rising and narrowing of the ship’s bottom are determined with a mezzaluna, as already mentioned. Interestingly, the division of the arc of circle used in the construction of the graminho is done by trial and error, as described in sixteenth century texts: “and if the divisions are not right, one must make them again, longer or shorter, (…) until they divide the graminho [here meaning the half circle] exactly into the right number [of predesigned frames]” (Oliveira 1991, folio 95).

Mestre Edi traced a graminho for us, to show how they do it, and after establishing the total rising, which is the radius of the half circle, he traced it and proceeded to divide each half into four equal parts with the compass. The first attempt was too long, a second hardly a bit too short, and the third absolutely precise. I asked him if he knew any other way to divide the arc of circle into equal parts and he was clear that this is the fastest and most precise.

Bevels (sotamentos) are cut with the help of a scale marked in the graminho. The floor timbers are fashioned a little bit thicker than the mold to allow the beveling, which is taken from the molded dimension (de cheio), and the futtocks are cut from the original design thickness (de solinho). All bevels are marked with the help of a bevel gage (suta) at certain points along the length of the timbers and traditionally adzed out. Today carpenters tend to use electric belt sanders. The bevels seem to be measured directly from the graminho on the floor timbers and futtocks, but at least in some cases they are increased along the futtocks, being more pronounced on the top than the bottom sections.

As was mentioned above, the most important design dimension is the length on deck. The keel length results from the shape and rake of the posts. All Valença shipwrights seemed to use the metric system.

After laying the stem post, the bow and stern knees, and the stern panel, the already beveled predesigned frames are mounted over the keel in a manner similar to the one described above. These frames are then carefully aligned and levelled, with the help of a symmetrical bipod and plumb bob. The bottom of the bow floor timbers is beveled, as mentioned in step six of Sarsfield description, so that they are inclined forward, in order to make more space on the deck. The alignment of the frames is extremely important because once it is done, the keelson is fastened to the keel and the ribbands (armadouras) are nailed to the frames in a way that ensures a perfectly symmetrical grid from which the bow and stern frames (enchimentos) are shaped. In the smaller river boats we have observed, the mast step is just a mortise on the upper face of the keelson. In larger boats it is a transversal timber laid over the keelson.

The main wale (cinta) is fastened to the complete framing, bent with the help of ropes and clamps, augured and fastened with screws – bolts in the past. When timbers need to be bent, shipwrights use fire (quentura), oil, and weights, keeping the portion of the timber over the fire permanently wet.

In larger ships a second wale is laid under the main wale, opposite to the deck clamp (dormente). A stringer is fastened over the floor-futtock overlap area, and the deck beams (latas) are dovetailed into the clamp, or simply fastened to the main wale from the outside. Around the main hatch the deck beams (vaus) run between the deck clamp and a longitudinal timber named suporte da braçola. A waterway (tabica) is then laid, above which the futtocks – reduced to every other futtock – are designated as cabeços.

The planking starts from the main wale and is laid downwards. According to mestre Chico, after laying four planks under the mainwale, another four planks are laid from the keel upwards, and a ninth, drop plank is then laid to close the hull. Spiling (fasquilhar) is done with a thin ribband (fasquilha), from which offsets are measured at each frame. Room and space on a 10 m long saveiro was 25 cm in the predesigned frames and 35 cm in the bow and stern enchimentos. The measurements are transferred to the inner face of the plank being shaped. The garboards (tábuas de resbordo) are sometimes laid last, with a characteristic sharp angle on the forward hood. There is no rabbet (alefriz) along the keel. Only the bow and stern knees have rabbets to receive the planking hoods.

The deck is planked in the final construction stage, and in case there is a mast, a thicker longitudinal plank (tamborete) is used as a mast partner. The final timbers are the bulwarks (borda falsa), caprail (corrimão), and stern post, which receives the rudder. The construction of a 15 m saveiro takes around 120 days (mestre Zé Crente pers. comm.).

Although the common trait that all the ships and boats inspected – mainly saveiros, barcos and escunas – share is the use of graminhos to obtain a fair lower hull shape through a non-graphic process (without any drawings), many other traits and gestures we observed are obviously shared by the shipwrights interviewed. In some cases it was clear how they learned a certain technique – such as how much to bevel the bottom of the floor timbers in order to get a wider deck, as explained above – and how they changed it a little bit, to get a shape more to their taste, and passed it down to their apprentices.

The simplicity of this technique is evident in this preliminary study, and although all shipwrights change it here and there, in the number of predesigned frames, in the intended draft, or in the way the turn of the bilge arc is obtained, the basic technique of obtaining the shape of a boat’s hull using molds and ribbands remains unchanged since it was described in 15th and 15th century documents. At this point it is not known when this process was brought to Brazil. Not all shipwrights interviewed descended from families of shipwrights. Only further archival research will facilitate a better understanding of this question.

Bahia 2014

In 2014 Samila Ferreira and Rodrigo Torres visited Valença and interviewed shipwrights, collected drawings and video, and amassed an important dataset on the lives and carperter skills of the community.

Projeto IÇAR

Project Içar is a project started and managed by architect Marcelo Bastos, aiming at the recording, study and protection of the last Saveiros da Baía de Todos os Santos.

References

Alves, F., Rieth, E., Rodrigues, P., Aleluia, M., Rodrigo, R., and Garcia, C., 2001. “The Hull Remains of Ria de Aveiro A, a Mid-15th Century Shipwreck from Portugal: a Preliminary Analysis.” In Proceedings of the International Symposium ‘Archaeology of Medieval and Modern Ships of Iberian-Atlantic Tradition’, ed. by F. Alves. Lisbon: Instituto Português de Arqueologia.

Agostinho, P., 1973. Embarcações do Recôncavo: um Estudo de Origens. Salvador: Museu do Recôncavo Wanderlei Pinho.

Agostinho, P., 2011. Embarcações do Recôncavo: um Estudo de Origens. Salvador: Oiti Editora.

Anderson, R. C., 1925. “Italian Naval Architecture about 1445”, Mariner’s Mirror 11:135-163.

Anderson, R.C., 1945. “Jal’s Memoire no. 5 and the Manuscript ‘Fabrica di Galere’,” Mariner’s Mirror, 31:160-167.

Barata, J., 1989. Estudos de Arqueologia Naval, 2 Vols., Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda.

Barker, R.A., 1993. “John Patrick Sarsfield’s Santa Clara: an addendum” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 22.2: 161-165.

Barker, R.A., 2001. “Sources for Lusitanian shipbuilding” in Francisco Alves, ed., Proceedings of the International Symposium ‘Archaeology of Medieval and Modern Ships of Iberian-Atlantic Tradition’, Lisbon, 1998. Lisbon: IPA: 213-228.

Batchvarov, K., 2009. The Kitten Shipwreck: Archaeology and Reconstruction of a Black Sea Merchantman, Dissertation, Texas A&M University, pp. 144-161.

Batchvarov, K., 2014 “The Hull Remains of a Post Medieval Black Sea Merchantman from Kitten, Bulgaria,” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 43.2: 397-412.

Bondioli, M., 2003. “The Art of Designing and Building Venitian Galleys from the XVth to the XVIth Centuries”, in Proceedings of the IX International Symposium on Boat and Ship Archaeology, Venezia 2000, edited by C. Beltrame. Oxford: Oxbow.

Carrell, T. and Keith, D., 1992. “Replicating a ship of discovery: Santa Clara, a 16th-century Iberian caravel,” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 21.4: 281-294.

Castro, F., 2005. The Pepper Wreck. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

Castro, F., 2007. “Rising and Narrowing: 16th-Century Geometric Algorithms used to Design the Bottom of Ships in Portugal”, International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 36.1: 148-154.

Castro, F., Yamafune, K., Eginton, C., and Derryberry, T., 2011. “The Cais do Sodré Shipwreck,” in International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 40.2: 328-343.

Ciciliot, F., 2000. “Genoese shipbuilders in Portugal and in Asia (early 16th Century)”, in Fernando Oliveira e o seu tempo. Humanismo e arte de navegar no Renascimento Europeu (1450-1650), Actas da IX Reuniao Internacional de Història da Nàutica e da Hidrografia, Cascais: Patrimonia: 153/161.

Crumlin-Pederson, O., 1991. “Ship Types and Sizes,” in Crumlin-Pedersen, O., ed., Aspects of Maritime Scandinavia, AD 200-1200, Proceedings of the Nordic Seminar on Maritime Aspects of Archaeology, Roskilde 1989., Roskilde, Denmark: Roskilde Museum.

Damianidis, K., 1998. “Methods used to Control the Form of the Vessels in the Greek Traditional Boatyards”, in Rieth, Eric, Technologies / Ideés / Pratiques: Concevoir et Construire les Navires, Érès, Ramonville Saint-Agne: 217-244.

Dawkins, Richard, The Selfish Gene. Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1976.

Dell’Amico, P., 2002. Construzione navale antica, Albenga: Edizioni del Delfino Moro.

Dias, D., 2009. Os segredos da arte. Feira de Santana, Bahia: UEFS Editora.

Fernandez, M., 1989. Livro de Traças de Carpintaria, 1616, Fac-simile, Lisboa: Academia de Marinha.

Filgueiras, Octávio Lixa, 1989. “Gelmirez e a reconversão da construção naval tradicional do NW Sec. XI-XII: Seus prováveis reflexos na época dos Descobrimentos”, Actas do Congresso Internacional Bartolomeu Dias e a sua Época, 2: 539-576, Porto: Universidade do Porto, Comissão Nacional para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses.

Hocker, F., 1991. The Development of a Bottom-Based Shipbuilding Tradition in Northwestern Europe and the New World, Dissertation, Texas A&M University, pp. 245-247.

Hocker, F., 1992. “The Brown’s Ferry Vessel: A River Transport of the Early Eighteenth Century,” INA Quarterly 19.1: 10-14.

Jal, A., 1840. Archéologie Navale, Paris: Arthus Bertrand Éditeur.

Lane, F.,1934. “Naval Architecture about 1550,” Mariner’s Mirror 20:24-49.

Lavanha, J., 1996. Livro Primeiro de Architectura Naval, Fac-simile, transcription and translation into English, Lisboa: Academia de Marinha.

Loewen, Brad, 1994. “Codo, carvel, mould and ribband: the archaeology of ships, 1450-1620”, Mémoires-vives, 6-7: pp. 6-21.

Loewen, B., 1998, The Morticed Frames of the 16th-Century Atlantic Ships and the ‘Madeiras de Conta’ of Renaissance Texts, Archeonautica 14, 213–22.

Macaulay, David, 1993. Ship. Boston : Houghton Mifflin.

McManamon, J., 2001. “The “Archaeology” of Fifteenth-Century Manuscripts on Shipbuilding,” INA Quarterly 28.4: 17-26.

Nance, J., 1992. “The Columbus Foundation’s Nina: A report on the rigging and sailing characteristics of the Santa Clara,” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 21.4: 295-308.

Oliveira, F., 1991. O Liuro da Fabrica das Naos (1580), Fac-simile, transcription and translation into English, Lisboa: Academia de Marinha.

Olaberria, J., and Olaizola, I., 2013. “A Basque Shipyard Design Method of the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries, and its Relationship to Non-Graphic Hull Design in the 15th Century,” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 42.2: 358-364.

Palacio. Diego G. de, 1587. Instrvcion navthica

para el bven vso, y regimiento de las naos, su traça, y gouierno conforme à la altura de Mexico Mexico: En casa de Pedro Ocharte.

Prieto, J. Nieto, and X. Raurich, eds., 1989. Excavacions arqueològiques subaquàtiques a Cala Culip, I., Girona: Centre d’Investigacions Arquelògiques de Girona.

Rieth, E., 1996. Le Maître-gabarit, la Tablette et le Trebuchet. Éssai sur la conception non graphique des carènes du Moyen-Âge au XXe siècle. Paris: Comité des Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques.

Rieth, E., 1998. “Construction navale à Franc-Bord en Méditerranée et Atlantique (XIVe-XVIIe siècle) et ‘Signatures Architecturales’ Une Première Approche Archéologique”, in Rieth, E., ed., Méditerranée Antique. Pêche, Navigation, Commerce, Paris: Comité des Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques.

Rieth, E., 2004. “Des Mots aux Pratiques Techniques. Gabarit et architecture navale au Moyen Age” in Chronique d’Histoire Maritime 56: 13-34.

Sarsfield, John P., 1984. « Notes: Mediterranean Whole Molding » Mariners’ Mirror 70.1 : 86-88.

Sarsfield, John P., 1985a. “Survival of Pre-Sixteenth Century Mediterranean Lofting Techniques in Bahia, Brasil” Octavio Lixa Filgueiras, ed., Forth Meeting of the International Symposium on Boat and Ship Archaeology, Lisbon.

Sarsfield, John P., 1985b. “From the Brink of Extiction” Wooden Boat 66: 84-89.

Sarsfield, John P., 1991. “Master Frame and Ribbands” in Reinder Reinders and Kees Paul,eds., Carvel construction technique: skeleton-first, shell-first : Fifth International Symposium on Boat and Ship Archaeology, Amsterdam 1988. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Smarcevski, L., 1996. A alma do saveiro. Salvador: Odebrecht.

Sosson, Jean-Pierre, 1962. “Un compte inédit de construction de galères à Narbonne (1318-1320), Bulletin de l’Institut Historique Belge de Rome, p. 57-318.