Naval Ram Collection

Stephen DeCasien

Ph.D. Student – Nautical Archaeology – Texas A&M University

Communications – RPM Nautical Foundation

Introduction

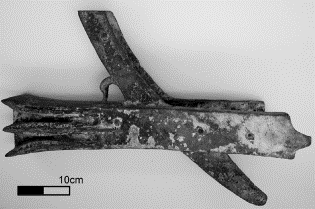

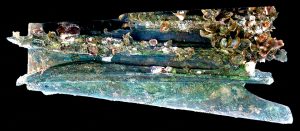

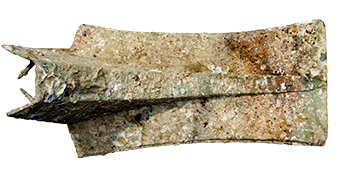

In antiquity, the naval ram was a weapon that dominated Mediterranean naval warfare for nearly five hundred years. The use and devastating force of the ram is evidenced in the ancient sources, but the former weapon was not discovered by archaeologists until the 1980s. The first archaeologically attested ram was discovered off the coast of Atlit, Israel, warranting this artifact to be called the Athlit ram. The Athlit ram was the first ram to be studied by archaeologists and historians. The Athlit ram and its intact bow timbers revealed that the ram was an integral part of warship construction and a complex naval weapons system. The Athlit ram indicated that rams were casted in the indirect lost wax casting method and were typically casted to the highest standards in antiquity. A multitude of rams have been found since the recovery of the Athlit ram, predominantly on the seafloor with the exception of a unique discovery in a dentist’s office. Each subsequent ram discovery has helped scholars to gain deeper insights into naval warfare from the Classical to the early Roman Imperial periods.

Kasyna online w Polsce to świetny sposób na cieszenie się ulubionymi grami w kasyno depozyt skrill bez wychodzenia z domu. Oferują również różne bonusy i promocje, aby przyciągnąć nowych graczy i utrzymać ich lojalność. Jednak ważne jest, aby przed rozpoczęciem gry sprawdzić, czy kasyno online jest legalne i licencjonowane przez wiarygodny organ regulacyjny. Pierwszym krokiem jest wybór kasyna online, które akceptuje graczy z Polski. Istnieje wiele popularnych witryn oferujących tę usługę, ale wybór najlepszej opcji należy do Ciebie. Powinieneś także znaleźć witrynę, która oferuje obsługę klienta w Twoim ojczystym języku. Rozpoczęcie pracy Jednym z najlepszych sposobów na rozpoczęcie gry w kasynie online jest gra za darmo. Da ci to szansę na zapoznanie się z oprogramowaniem i zasadami gry. Następnie możesz spróbować szczęścia w grach na prawdziwe pieniądze. Kilka wskazówek, jak najlepiej wykorzystać swoje doświadczenie Najlepszym sposobem na maksymalne wykorzystanie hazardu jest gra w renomowanym kasynie, które oferuje szeroką gamę gier i bezpieczne opcje bankowe. Dzięki temu Twoje doświadczenia będą bezpieczniejsze i wygodniejsze. Kolejną wskazówką jest gra z bankrollem. Pomoże Ci to ustalić limit, ile możesz wydać na hazard. Pomoże Ci to również uniknąć wydawania więcej, niż możesz sobie pozwolić. Istnieje wiele różnych rodzajów gier, w które można grać w kasynie online w Polsce, w tym automaty do gry, gry karciane i gry stołowe. Do najpopularniejszych należą poker, blackjack i ruletka. Powinieneś także spróbować swoich sił w grach zręcznościowych, ponieważ są one świetnym sposobem na wygranie gotówki. Są bardzo podobne do pokera wideo, ale zawierają trochę więcej strategii. Możesz grać w te gry za darmo w wielu kasynach online w Polsce, więc koniecznie sprawdź je przed wpłatą pieniędzy. Następną wskazówką jest upewnienie się, że kasyno online, które rozważasz, wykorzystuje najnowszą technologię do ochrony Twoich danych. Zapobiegnie to kradzieży lub manipulacji Twoimi danymi osobowymi przez hakerów. Jeśli chcesz używać smartfona do grania w gry kasynowe, zalecamy pobranie aplikacji mobilnej ze strony internetowej kasyna. Aplikacje są zwykle bezpłatne i łatwe do zainstalowania na urządzeniu. Oprócz pobrania aplikacji mobilnej upewnij się, że kasyno, które rozważasz, jest kompatybilne z Twoim urządzeniem. Większość najlepszych kasyn online w Polsce ma zoptymalizowane strony internetowe i jest przyjazna dla urządzeń mobilnych. Poza tym powinieneś poszukać kasyna online, które akceptuje preferowaną metodę płatności. W Polsce gracze mogą korzystać z e-portfeli, takich jak Skrill czy Neteller, aby dokonywać wpłat i wypłat. Dzięki temu proces będzie szybszy i bezpieczniejszy, ponieważ są w stanie zaszyfrować Twoje pieniądze. Ponadto mogą służyć do wysyłania płatności i przesyłania środków między rachunkami.

The following is a recent comprehensive list of all the archaeologically attested naval rams from antiquity (for further information on each ram, see bibliography). There are currently 33 rams that exist in the archaeological record, many of which are authentic three-bladed waterline rams. Not all of these rams are provided in the list as some have yet to be recovered from the seafloor or given a proper designation and/or publication. Most of the rams listed have either been recovered or are continuing to be found at the battle site of the Egadi Islands near Western Sicily by RPM Nautical Foundation in cooperation with the Sicilian government and the Soprintendenza del Mare. The list comprises the Bremerhaven, Athlit, Piraeus, Acqualadroni, and Follonica rams; the Belgammel proembolion, a ‘subsidiary’ ram; and a myriad of other Egadi rams.

*Egadi Ram Images Courtesy of RPM Nautical Foundation.

Naval Rams

Bibliography

Adams, J., et al. “The Belgammel Ram, a Hellenistic-Roman bronze proembolion found off the coast of Libya: test analysis of function, date and metallurgy, with a digital reference archive.” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 42 (2013): 60-75.

Bockius, R. “Der “Bremerhaven-Rammsporn”. Ein exzeptionelles Relikt antiker Seekriegsführung im Museum für Antike Schiffahrt Mainz und seine Parallelen.” Jahrb. RGZM 61 (2014), 57-101.

Buccellato, C. and Tusa, S. “The Acqualadroni Ram Recovered Near the Strait of Messina, Sicily: dimensions, timbers, iconography and historical context.” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 42 (2013): 76-86.

Casson, L. and J. Steffy. The Athlit Ram. College Station: Texas A&M U. P., 1991.

Casson, L. Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1971.

Mark, S. “The earliest naval ram.” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 37 (2008): 253-272.

Morrison, J. The Age of the Galley. London: Conway Maritime, 2004.

Morrison, J., and R. Williams. Greek Oared Ships 900–322 BC. Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 1968.

Morrison, J., J. Coates, and N. Rankov. The Athenian Trireme. Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 2000.

Murray, W. The Age of Titans. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 2012.

Murray, W., and P. Petsas. “Octavian’s campsite memorial for the Actian War.” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 79 (1989): 1-172.

Murray. W. “The weight of trireme rams and the price of bronze in fourth century Athens.” Greek Roman and Byzantine Studies 26 (1985): 141-150.

Murray. W., et al. “Cutwaters before rams: an experimental investigation not the origins and development of the waterline ram.” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 46 (2016): 72-82.

Oron, A. “The Athlit Ram bronze casting reconsidered: scientific and technical reexamination.” Journal of Archaeology Science 33 (2006): 63-76.

Oron, A. “The Athlit Ram: Classical and Hellenistic Bronze Casting Technology.” M.A. Thesis, Texas A&M University, 2001.

Prag, J. “Bronze rostra from the Egadi Islands off NW Sicily: The Latin inscriptions.” Journal of Roman Archaeology, 27 (2014): 33-59.

Pridemore, M. “The form, function, and interrelationships of naval rams: a study of naval rams from antiquity.” M.A. Thesis, Texas A&M university, 1996.

Royal, J., and S. Tusa, eds. The Site of the Battle of the Aegates Islands at the end of the First Punic War. L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2019.

Steffy, J. Wooden Ship Building and the Interpretation of Shipwrecks. College Station: Texas A&M U. P., 2006.

Tusa, S., and J. Royal. “The landscape of the naval battle at the Egadi Islands (241 B.C.).” Journal of Roman Archaeology 25 (2012): 7-48.