Cultural Heritage Law

Ole Varmer and Mariano Aznar

Introduction

The Nautical Archaeology Digital Library (NADL) started in 2006 as a repository of information useful to nautical archaeologists and 15 years later is trying to become a node in a global network of internet resources conceived to share reliable information with students and archaeologists around the world. This section provides information to both professionals and the public in general about ethical and legal protections of the world’s cultural heritage.

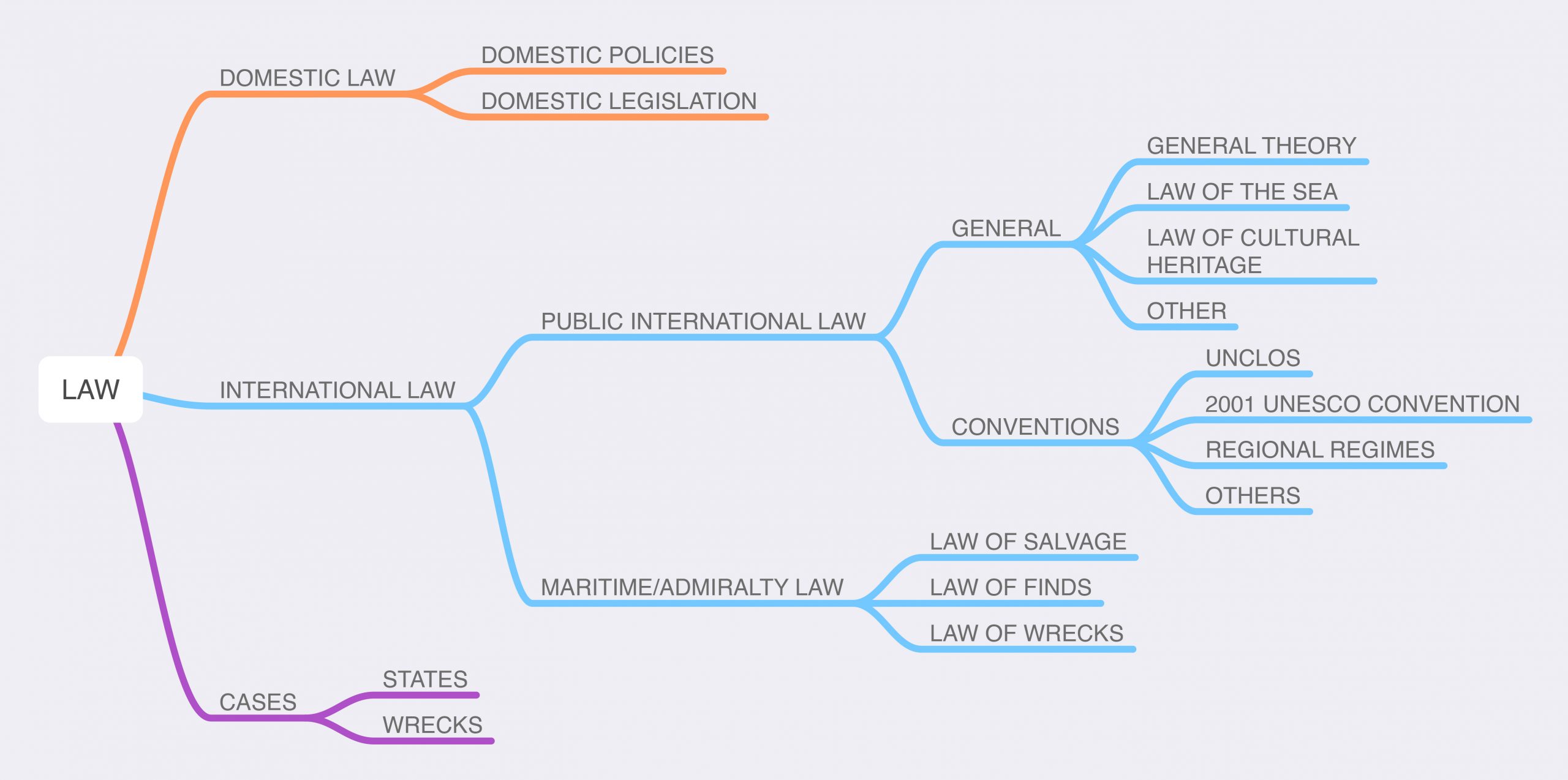

Law

The sources of domestic law or rules of a nation are generally found in statutes, codes, and the regulations of a particular nation. They may be further explained in administrative policies or in the cases of courts or administrative tribunals.

International Law: Public (the law of nations) and Private (e.g., maritime law of salvage law and Admiralty jurisdiction)

International law is the law agreed to between two or more nations. The sources are generally recognized practice of nations (customary international law) and treaties or conventions which are only binding on those nations that have become parties. Public international law includes those conventions regarding the activities and obligations of the national governments such as the 2001 UNESCO Convention. Private International Law pertains to private activities of companies or persons such as the maritime law of salvage. The public interest in protecting our cultural heritage is reflected in the international and domestic laws to protect it.

International Law (links on the website of the Advisory Council of Underwater Archaeology) The summaries of international law below are taken from Rivere, E., Dlamini, T., Kourkoumelis, D., Varmer, O., (2019) Evaluation of UNESCO’s Standard-Setting Work of the Culture Sector – Part VI – 2001 Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage. UNESCO Evaluation Office.

Public International Law

UN Convention on the Law of the Sea

The 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea is one of the most comprehensive and widely accepted international agreements. As noted by the legal experts interviewed, it has a constitutional nature providing the legal framework for the conduct of activities at sea, reflecting a careful balance of the corresponding rights, jurisdiction, and authority of coastal and flag States. However, it only has two short and very general articles on heritage, Articles 149 and 303; that were introduced towards the end of negotiations.

Article 149 recognizes the general legal principle for “objects of an archaeological or historical nature” in the “Area” beyond the jurisdiction of nations. It says that this underwater heritage must be “preserved or disposed of for the benefit of mankind as a whole.” It also says that States must recognize the preferential rights of certain other States that may have an interest in the heritage. However, it does not define these preferential rights, nor does it provide any details on how States are to implement the principle, or how those rights should be balanced. In short, it provides no standards for compliance.

Article 303(1) recognizes that States have a general duty to protect heritage found at sea and shall cooperate for that purpose. However, like Article 149, it provides little detail or guidance as to how States should act to protect such heritage and provides no standards of compliance. Subsection (2) does identify the limit of coastal State jurisdiction over the removal of submerged heritage within its 24 nautical mile contiguous zone. Article 303 subsection (3) clarifies that this article does not alter any rights of ownership or the law of salvage, and subsection (4) clarifies that it is without prejudice to other international agreements. A leading commentary on UNCLOS noted that “[p]resumably, in the course of time, this incipient new branch of law “[would] be completed by the competent international organization, above all UNESCO, and by State practice.” As such, the 2001 Convention could be interpreted as being lex specialis, which, although, subject to international law, could fill the gaps left by the UNCLOS regarding the protection of submerged heritage.

A primary purpose of the 2001 Convention was therefore to build on the legal framework of UNCLOS and provide details for implementing the duty to protect “objects of an archaeological or historical nature” and to cooperate for that purpose. Addressing the perceived gap in the protection of UCH in the EEZ and continental shelf was especially important. This included addressing the direct threat from looting and salvage that are not done in accordance with the scientific approach of archaeological standards. As many of those interviewed noted, the 2001 Convention provides the sorely needed details for protection, regulation, compliance and cooperation that are missing in UNCLOS. The evaluation of UNESCO’s Standard-setting work of the Culture Sector – Part VI – 2001 Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage (May 2019)(Evaluation of 2001 UNESCO Convention)

2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage

The 2001 Convention is the most comprehensive agreement to date to recognize and incorporate the UNCLOS framework and provide the needed details, standards and requirements for compliance in a manner consistent with it. The 2001 Convention may also be relevant or helpful guidance for other nations and international organizations as they carry out their work under UNCLOS, particularly in implementing UNCLOS Articles 149 and 303. A few experts highlighted how UNCLOS Article 311(3) limits the rights of State Parties to enter subsequent agreements, which are incompatible with the object and purpose of UNCLOS. This supports the view that the Parties to UNCLOS that are also Parties to the 2001 Convention consider the two instruments to be compatible or consistent. 50. A review of the provisions of the 2001 Convention reveals several express references to UNCLOS, incorporating the framework provisions and then building upon it. For example, the preamble identifies “the need to codify and progressively develop rules relating to the protection and preservation of underwater cultural heritage in conformity with international law and practice, including“[…] [UNCLOS];” Article 1 uses the UNCLOS terms “objects of an archaeological or historical nature” and expands upon them using other terms consistent with State practice,20 and Article 2 identifies the duty to preserve heritage under UNCLOS and provides more detail as to how to cooperate in implementing the duty to protect. Article 3 states that “[nothing in this Convention shall prejudice the rights, jurisdiction and duties of States under international law, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. This Convention shall be interpreted and applied in the context of and in a manner consistent with international law, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.” Evaluation of 2001 UNESCO.

Other Public International Law Conventions Relevant to Underwater Cultural Heritage

The 1954 Convention on the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict was the first worldwide treaty focussing on the protection of cultural heritage, movable and immovable. In implementing the 1954 Convention in peacetime or during a conflict, States Parties should undertake a number of measures such as undertaking inventories, conducting training for military and police, using the Blue Shield Emblem, and above all refraining from targeting cultural property during a conflict by not placing troops near it. All of these measures apply to cultural heritage, whether it is on land or under water.

1970 UNESCO Convention on Trafficking of Cultural Property

The 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property encourages States to cooperate to curb illicit trafficking. It is complemented by the international private law approach of the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects. Cultural objects found underwater continue to be looted, trafficked, and sold in art markets around the world. These “treasure hunting” operations directed at UCH are contrary to the 2001, 1970 and UNIDROIT Conventions. Interviews with UNESCO staff and representatives of international organizations working in law enforcement clearly show that by drawing on the synergies and partnerships amongst these three instruments, UNESCO’s approach and action to combat illicit trafficking of UCH has an enormous potential of being strengthened.

1972 UNESCO World Heritage Convention

The 1972 Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage links the conservation of natural and cultural properties and defines the criteria for these to be considered for inscription on the World Heritage List. A number of cultural and mixed World Heritage properties are located underwater and some of these are covered by the World Heritage Marine Programme. To date, this Programme has not included UCH in its scope of work. Yet, in 2010, the World Heritage Centre had highlighted that the ‘Programme, which is currently limited to natural sites of marine biodiversity, could […] enlarge its scope to submerged archaeological sites’. World Heritage Committee, World Heritage Convention and the other UNESCO Cultural Conventions in the field of Culture, 34th sess, Item 5E, Doc WHC-09/34.COM/5E (9 July 2010), para 26

2003 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage

Its aim is to safeguard a specific form of (intangible) heritage: practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, and skills that communities recognize as their cultural heritage. It is also a tool to support communities and practitioners in their contemporary cultural practices, whereas experts are associated only as mediators or facilitators. As a living form of heritage, the safeguarding measures for intangible cultural heritage aim, among other things, to ensure its continuing renewal and transmission to future generations. Under the 2003 Convention, States Parties art to define and inventory intangible cultural heritage with the participation of the communities concerned; adopt policies and establish institutions to monitor and promote it; encourage research; and take other appropriate safeguarding measures, always with the full consent and participation of the communities concerned. Again, there is a recognition of how cultural and natural heritage is intricately linked particularly to indigenous knowledge and the cultural practices Exploring the connections between the tangible and intangible aspects of UCH is essential in order to fully understand the cultural, historical and social value of these sites and to involve the local communities in their protection.

Private International Law (maritime law of salvage)

Maritime law is the substantive law that governs private maritime matters including salvage. It consists of both domestic and private international law. Some use the terms admiralty and maritime law interchangeably, but in its strictest sense admiralty refers to a specific court in England and the American colonies that had jurisdiction over torts and contracts on the high seas, whereas substantive maritime law developed through the expansion of admiralty court jurisdiction. Maritime law dates back centuries to the time of ancient Egyptian, Phoenician, and Greek ports due to the need for uniform rules for activities at sea and spread to Europe and beyond along with trade and commerce. The salvage law evolved from ancient codes to a 1910 Salvage Convention that evolved to the 1989 IMO Convention.

1989 IMO International Convention on Salvage and the 2001 UNESCO Convention

In 1989, under the auspices of the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the States interested in unifying the maritime law of salvage adopted the International Convention on Salvage, also known as the Salvage Convention. Article 1 defines “(a) Salvage operation [as] any act or activity undertaken to assist a vessel or any other property in danger in navigable waters or in any other waters whatsoever.” Under (b) Vessel means any ship or craft, or any structure capable of navigation.” Consistent with the long practice of nations, the Salvage Convention applies to recent maritime casualties, and not to submerged heritage resources that have been incapable of navigation for decades if not centuries. Regardless, in response to requests for provisions that specifically address UCH, Article 30(1)(d) of the Salvage Convention states that ―’’[a]ny State may, at the time of signature, ratification, acceptance, approval, or accession, reserve the right not to apply the provisions of this Convention “[…] when the property involved is a maritime cultural property of prehistoric, archaeological or historic interest and is situated on the sea-bed’’. In general, the Salvage Convention does not apply to State vessels, unless a State party notifies the IMO and specifies the terms and conditions of applicability. In addition, the Salvage Convention disclaims any effect on ― any provision of national law or any international convention relating to salvage operations by or under the control of public authorities.

The 2001 Convention is consistent with the 1989 International Maritime Organization Convention on Salvage

The IMO observer at the 1998 Paris meeting on the draft UNESCO Convention for the Protection of UCH reiterated the inapplicability of the Salvage Convention to historic shipwrecks, explaining: ‘’[T]he Salvage Convention is a private law Convention and its objectives are very different from those of [the 2001 UNESCO Convention] draft, which deals with international public law. The Salvage Convention should not, therefore, apply to historic wrecks.’’ Of course, it remains to each country to decide whether to apply the maritime law of salvage. A few of the experts interviewed for this evaluation noted that there was no conflict between the Salvage Convention and the 2001 Convention, but that there may be some benefits for increased cooperation between the IMO and UNESCO. For example, there could be cooperation in the education and outreach regarding mutual interest in maritime heritage and UCH, and in respect to the purpose, scope and application of each of these Conventions as well as the Nairobi Wreck Convention.

2007 IMO Nairobi International Convention on the Removal of Wrecks

A primary purpose of the 2007 International Convention on the Removal of Wrecks (Nairobi Wreck Convention) is clarifying the coastal State’s authority to address threats to navigation and marine pollution from wrecks outside its territorial sea from a sunken or stranded ship. Like the Salvage Convention, its focus is upon recent marine casualties. However, the Nairobi Wreck Convention may also apply if the wrecks have been underwater for at least 100 years. Shipwrecks, particularly from World Wars I and II, pose threats to the marine environment, e.g., bunker fuel, cargo that may be hazardous, and munitions. The Nairobi Wreck Convention recognizes the authority of States to remove, or have removed, shipwrecks that may have the potential to affect adversely the marine environment, navigation or its economic interests as well as the safety of lives, goods and property at sea. It therefore creates a set of uniform international rules aimed at ensuring the prompt and effective removal of wrecks

located beyond the territorial sea.

The 2001 Convention is consistent with the 2007 IMO Nairobi Convention on the Removal of Wrecks

Experts interviewed noted that there are no conflicts with the Nairobi Wreck Convention and the 2001 Convention or the Salvage Convention. In part, this is because the Nairobi Wreck Convention is about the coastal State authority to address threats of marine pollution and navigation off its coast and the 2001 Convention is about addressing the duty to protect UCH. In particular, the 2001 Convention recognizes that the coastal State has the discretionary authority on how to address this. The obligation under Article 5 is simply that the “State Party

shall use the best practicable means at its disposal to prevent or mitigate any adverse effects that might arise from activities under its jurisdiction incidentally affecting UCH’’. It was also noted that there are benefits to considering these conventions and some of the UN processes on the ocean, discussed below, as an integrated package. A couple of those interviewed found that the consideration for ratification of the Nairobi Wreck Convention and the issue of

potentially polluting vessels also helped in the consideration of the 2001 Convention as both are concerned about addressing threats to heritage (both natural and cultural).

Regional or Bi-Lateral International Agreements on UCH

International Agreement on RMS Titanic

The Law protecting RMS Titanic is highlighted as it is perhaps the most famous shipwreck. It is subject to the 2001 Convention as well a International Agreement between the United Kingdom and the United States. As it is located on the seabed under the high seas, it is a potential model for high seas Marine Protected Areas and how to fulfill the duty to protect UCH and cooperate for that purpose under customary international law as reflected in the Law of the Sea Convention. See also the UNESCO webpage on Titanic and the ACUA webpage on Titanic 100th Anniversary

The Barcelona Convention was adopted in 1976 in conjunction with two Protocols addressing the prevention of pollution by dumping from ships and aircraft and cooperation in combating pollution in cases of emergency. The

Convention’s main objectives are: to assess and control marine pollution; to ensure sustainable management of natural marine and coastal resources; to integrate the environment in social and economic development; to protect the marine environment and coastal zones through prevention and reduction of pollution, and as far as possible, elimination of pollution, whether land or sea-based; to protect the natural and cultural heritage. It was the first-ever Regional Seas Programme under the United Nations Environment Programme.

Ethics

Register of Professional Archaeologists Ethics Database: http://archaeologicalethics.org/

ACUA webpage on Ethics & Museum Standards