Santíssimo Sacramento (1647)

Chase Oswald, Filipe Castro, and Paulo Jorge Rodrigues

Country: South Africa

Place:

Coordinates: Lat. ; Long.

Type: Nau

Identified: Yes

Dated: 1552 (Historical accounts)

Introduction

Portuguese shipbuilding was in crisis in the second half of the 17th century. The scarcity of public funds prevented the state from building at least two ships per year, the minimum number necessary to keep the India Route.

It was in this context that the galleon Santíssimo Sacramento was commissioned to Rui Dias da Cunha by the Governor of Bassein, D. Telles de Menezes. According to the Regiment of 23 February 1615 the contract required a particular shape and size, with four masts and a high stern castle, as defined in Lisbon.

The keel was laid down at Bassein, in 1638, and the hull was ready by early 1640. The ship was launched in April and towed south, to Goa, where the upper works and the rigging were to be completed. War with the Netherlands delayed the completion of the ship several years, but it was ready in 1646 and it was said that it was a large and beautiful ship, although some complained that it was difficult to maneuver because of its size.

Sacramento‘s artillery was chosen from the best and most powerful guns available. Some guns were purposely cast. When it was ready it armed two batteries on each side, making a total of 60 guns. Dutch spies, probably ill-informed by carefully placed counter-information, believed that Sacramento carried 80 guns.

Finally, in the last days of January 1647 Sacramento was anchored alongside the old ship Nossa Senhora da Atalaia do Pinheiro, ready to leave as soon as Sacramento was loaded. A number of bronze guns was loaded as cargo, cast by the famous gun maker Manuel Tavares Bocarro, shipped to the kingdom.

The small fleet of two ships left Goa on February 20, 1647, already late in the season, and for that exposing itself to the rigors of the southern winter in the passage of the Cape of Good Hope. Sacramento‘s captain was Luís de Miranda Henriques, also captain of the fleet, while Nossa Senhora da Atalaia do Pinheiro was commanded by Admiral António da Câmara de Noronha, who had arrived in India as acptain of the galleon São Lourenço. The fleet carried a large cargo of Chinese ceramics and porcelains, 60 to 80 cannons cast by Tavares Bocarro, and a vast array of silks, cottons, precious woods, spices, drugs, gold – mostly in chains and rings – and precious stones.

A few days after leaving port the fleet spotted a ship with pilgrims to Mecca, which Luís de Miranda Henriques resolved to board and loot, against the advise of the other officers. The ship had a letter of safe conduct from the Portuguese authorities and the oficers from Atalaia convinced Henriques to spare the lives of the pilgrims. Beyond the loss of three days, this cruel incident demoralized the crews of both ships.

Three and a half months, near the equator, a third ship São Pedro o Grande, which had left Goa on March 6, caught up with the small fleet and sailed together for 20 days. Given the late date in the season, however, the captain of ão Pedro, Luis Botelho Fróis, decided to turn back and sail to Mozambique, to spend the winter. In the following year, sailing to Lisbon Fróis almost shipwrecked while passing the Cape, and had to head for Brazil, to repair his ship, after which he finally sailed back to Lisbon, shipwrecking in the Azores, in 1651.

Meanwhile, Sacramento and Atalaia were separated by a storm on June 12 and eventually both were thrown against the coast. It is difficult to know what really happened because the only written account that survived was written by Bento Teixeira Feio, from stories he later heard from the small group of survivors who joined the survivors of Atalaia, during the hard walk to Mozambique.

According to these survivors, on the night of the 12th to the 13th of June, after losing sight of Atalaia, the storm destroyed the mainsail and beat the galleon so hard that it started taking water in. As soon as that storm subsided the crew repaired the leaks and the ship continued its voyage south, in the direction of the Cape of Good Hope.

On the night of June 15 another storm hit the ship and it pushed south in view of land, sometimes too close for comfort. The ship held it course but on the night from June 29 to 30 the wind pushed it ashore and threw it against the rocks by 43 degrees of latitude south, at Algoa Bay, near today’s Port Elizabeth, near the Cape of Good Hope.

Only 72 people survived. After resting 11 days on the beach the survivors decided to walk to Mozambique and started a deadly march north. Almost five months later, on November 27, only nine persons were still alive when they encountered the survivors of Nossa Senhora da Atalaia in Zululand.

In 1778 the captain of a Dutch garrison stationed nearby visited Algoa Bay and marked the wreck site on a map, referencing the location of huts built by the survivors.

In 1949 an article referred to the existence of a gun and two anchors in the tidal area, and three years later a researcher named Harraway raised an iron gun from the site.

In 1977 David Allen and Gerry van Niekerk located 21 bronze guns under water in front of the site of Harraway’s gun. Soon after, this number rose to 61 when David Allen found another 40 guns – 21 of iron and 19 of bronze.

Account

Following their 1647 departure from Goa to Portugal, the galleon flagship, Santissimo Sacramento (under Commodore Luis de Miranda Henriques) and her consort ship, Nossa Senhora da Atalaia (captained by Antonio da Camara de Noronha) wrecked while attempting to round the Cape of Good Hope (Theal, 1902: 297). The account herein was originally written by Bento Teyxerya Feyo, a treasury official in India who survived the wrecking of Nossa Senhora da Atalaia and detailed his tale to King João IV, who promptly requested a written report (Duffy, 1955: 42-43).

On February 20th, 1647, Santissimo Sacramento and Nossa Senhora da Atalaia set out for Portugal, carrying the viceroy of Portuguese India Dom Filippe Mascarenhas from Goa (Theal, 1902: 297). The ship sailed along the Indian coast towards the north-west and kept this course with favorable winds to a latitude of 10 and 1/3°, north (Theal, 1902: 297). At dawn on March 2nd, Santissimo Sacramento spotted a foreign vessel and the commodore raised a flag and sail before firing two blank shots, forcing the foreign ship to furl her sails and send forth a boat to parley. The Portuguese ships drifted alongside this vessel for four days and nights while the commodore considered capturing it, though she carried a license under the viceroy and belonged to the king of Masulipatam, from which the State of India received substantial resources through his acquisition of Ceylon (Theal, 1902: 297 – 298). However, the officers of Nossa Senhora da Atalaia disagreed with the commodore’s intentions and argued that the foreign vessel should be allowed to continue her voyage. Therefore, on March 5th, the Portuguese departed from this foreign vessel at the urging of more seasoned mariners who wished to avoid rounding the cape in winter when tempests are more numerous and vicious. After crossing the equator the Portuguese sailed onward with heavy rains and calms during which time the galleon São Pedro overtook them, even after having left Goa fifteen days after their departure. São Pedro stayed alongside Santissimo Sacramento and Nossa Senhora da Atalaia for 20 days before parting ways (Theal, 1902: 298).

On April 19th, Easter Sunday, the captain of Nossa Senhora da Atalaia commanded that they give the Santissimo Sacramento a seven-gun salute. Instantly following this act, the Nossa Senhora da Atalaia sprang a leak, accumulating four hands of water (about 4 m), which was pumped out twice a day by the ship boys and slaves (Theal, 1902: 298). On June 10th, with ideal winds, the Portuguese reached a latitude of 33° South; however, the main topmast of the Nossa Senhora da Atalaia broke and due to this and the leaking hull, the Nossa Senhora da Atalaia requested that Santissimo Sacramento remain with them for a week while they attempted to repair the mainmast. However, due to rough weather conditions, they were unable to repair the mast (Theal, 1902: 299). By June 12th, eight sailors, five artillerymen, four ship boys, and several passengers had already died of sickness. As night fell on the 12th, a breeze fell just before sunset as the Portuguese were sailing towards land with a west-north-west wind; the sky became red as thick black clouds rolled in and a flash of lightning illuminated an orelhão fish (moonfish), an omen indicating to the Portuguese that a grave storm was upon them. Soon the wind began to roar, and in response the Nossa Senhora da Atalaia furled her topsails and spritsail. The sea began to rise and the wind surged, pitching the ship so much that she took on vast quantities of water. Commands were given to take down the main yard, furious hurricane of wind violently carried away the mainsail and foresail and tore them to pieces. The ship remained at the mercy of the waves until the crew eventually raised a storm-sail on the foremast, and positioned the main yard half-mast high with its sail taut top to bottom (Theal, 1902: 299).

The ship remained in this pummeled state for the rest of the night, straining its hull and taking on at least 10 hands of water (about 10 m) (Theal, 1902: 299-300). By the next morning, Nossa Senhora da Atalaia found herself alone, without the company of Santissimo Sacramento. As the storm continued to rage on through the next night, Nossa Senhora da Atalaia was beaten by the winds and the waves, battered by hailstones, and at the mercy of thunder and lighting. The ship continued to run with the wind astern as the crew managed to remove the remaining canvas from the spritsail yard and replace it with a new one. Over the next two days, they vigilantly worked the pumps as the weather calmed and Nossa Senhora da Atalaia sailed within view of land at a latitude of 32°. For the next few days, the crew sailed towards land with hopes of repairing the ship, pumping out its water, and sustaining themselves by fishing. At this time the master of the ship Jacinto Antonio thought it might be best to put back to Mozambique before the weather worsened again, secure the king’s property, save the ship, and obtain aid for the sick and injured. However, the master’s wishes displeased most aboard the ship many of when had business back in Portugal and cinnamon in the cargo that they wished to keep from spoiling, and so they coerced the master and those who agreed with him into maintaining their course to Portugal. Sailing south for the next few days Nossa Senhora da Atlaia increased her latitude in order to double the Cape. Everyone aboard the ship took shifts working the pumps so that they never ceased emptying the hold. The crew attempted to draw water out of the hold by converting barrels into buckets and clearing artillery hatchways to use as wells, but these efforts were of little help, due to four stored guns that blocked the hatchways (Theal, 1902: 300-301).

At this time rumors spread among the crew and passengers that many of the ship’s deck knees were broken. It was agreed that Nossa Senhora da Atalaia should seek a different latitude with improved weather so that the crew could rid the ship of water (Theal, 1902: 301). Shortly after, the master, officers, and captain went below deck to inspect the hull, returning with three nails in hand and exclaiming that “the ship was fit to go to Jerusalem” (Theal, 1902: 301). Nothing more was discussed about their journey, aside from the need to reach Portugal as soon as possible. The foresail was set on the evening of June 29th to steer the ship back towards land. The second pilot let the pilot know that land was near, and the latter replied that they had nothing to fear as he had navigated this coast for a long time. Before long a sailor on lookout, shouted “veer off, brothers,” as the ship found itself upon a shoal, in eight fathoms (about 15 m) of water, in the sea off Algoa Bay. The crew hastily unfurled the main-top-sail. Guided by the second pilot stationed at the cross-trees, they were able to get Nossa Senhora da Atalaia back to sea with the aid of a landward breeze and the efforts of all aboard (Theal, 1902: 301).

Unfortunately, due to this event, the ship now leaked more than before, with water coming in every seam (Theal, 1902: 302). This problem was magnified as a storm approached the following day, forcing every pump to work endlessly. As the storm raged on, Nossa Senhora da Atalaia sailed using her fore storm-sails but pitched so fiercely that the crew feared she would break amidships at every hour. The storm was so violent that it carried the waves over the lantern and masts on the stern. At the helm, the second pilot found himself alone, and almost drowned by the waves as the rest of the crew attended the pumps. Although those aboard the ship were few in numbers, they never ceased to work the pumps at this time. The officers maintained the starboard pump, the ship’s boys worked the larboard pump and the African slaves managed the wheel pump, whose chain broke every hour (Theal, 1902: 302). As the night-watch approached the slaves were commanded to maintain the pumps throughout the night; however, due to exhaustion, only two men worked the pumps. As the water increased during the night, the men at the pumps tried to warn the others but were ordered to not cause a disturbance amongst the ship. As day broke the crew opened the large hatchway and found the water now raised above the ballast. More barrels were then converted into buckets to remove the rising water, but again these efforts proved fruitless over the next two hours as the ship took on more water with every pitch. Eventually, Nossa Senhora da Atalaia took on so much water that the pepper holds burst, choking the pumps and rendering them useless. The crew continued to attempt to remove the water using barrels worked with the capstan, but this had little effect in reducing the ever-incoming volumes of water. Meanwhile, abaft of the mainmast, the crew opened a hatchway and attempted to remove the water using two tubs but ended up retrieving more pepper than water (Theal, 1902: 303).

In these conditions, the ship’s bow sank and now refused to heed the commands of the helm. Below, the water covered the hatch coamings of the bow and the lower hatches by at least two hands above the lower deck. Nossa Senhora da Atalaia spent two days and nights in this condition before spotting land. At daybreak on the third day, the crew sighted a thickly wooded ridge at the mouth of a river with a long sand beach and large bay, in which they assumed that they could land using the ship’s boat. However, due to the dilapidated state of the ship, it was decided that the Portuguese would run her ashore by throwing the artillery into the sea, which was all pointed through the portholes. This effort proved beyond the abilities of the crew and only two pieces were thrown from the ship. With favorable winds but rugged waves, the crew unfurled the main topsail, which shredded to pieces as they hoisted it, as did the fore-topsail, spritsail, foresail, and finally the mainsail (Theal, 1902: 303). Meanwhile, the captain had ordered the gunner to put powder and balls in barrels, and collect all the arms, copper, and bronze for the securing of a campsite, should they survive the landing and need to barter with the indigenous peoples (Theal, 1902: 303-304). The following night was spent removing as much water as possible with buckets, to buy time for a landing, while native campfires could already be seen lit on the nearby shore. By the next morning, July 2nd, the Portuguese prepared the boat for landing some of their people. Raising the anchor as the wind arose, they went landward with the foresail set and cast anchor in the bay at seven fathoms (about 13 m) of depth. Under the command of the master, the main halyards were cut and the yard was cut into pieces as it might aid those going ashore. The boat was launched with those among it armed with weapons and provisions so that they could secure a site onshore. Meanwhile, those who remained on board continued to man the pumps, buying as much time as possible. By the time the boat reached the breakers, it was already late in the day and the current revealed itself incredibly strong, forcing them to return to Nossa Senhora da Atalaia. As the tide retreated after nightfall the ship struck ground, damaging the rudder. In response, the crew cut down the main and foremasts, while casting out another anchor to prevent getting dragged out to sea. As the tide came back in the ship began to float in eight fathoms of water, again. After daybreak on July 3rd, the Portuguese gathered all the thin ropes and configured them into a surf-line, while also collecting people, weapons, and portable valuables. With one end of the surf-line tied on board the ship, the small boat was rowed towards the shoreline with great caution, as the surf around the breakers was powerful. Those among the boat reached the shore safely without interference since no natives were present. Upon landing they stored all that they could carry upon the shore before returning to the ship to retrieve the captain, noble ladies, and enslaved people still on board (Theal, 1902: 304).

Those in good health spent the day going back and forth in the boat, while others remained onshore to guard the cargo being landed and assist those working the boat. Many still on Nossa Senhora da Atalaia were too weak to help in the transporting of the cargo, which resulted in much of the provisions being left aboard. Of the more than 1000 bags of rice, only 30 were brought ashore. The boat made four trips ashore this day, the last trip hauling approximately 70 men, including the ship’s officers, members of the church, and numerous slaves. This last trip to shore met with great difficulty, as the boat was loaded to the gunwales. That night renewed stormy weather meant extreme danger for the chaplain and several other men who remained on board Nossa Senhora da Atalia.

On the morning of July 5th, many who had spent the night on the shore took to the boat to return to Nossa Senhora da Atalaia to load provisions. Using the surf-line the boat arrived safely to the ship; however, during the return trip a Chinese slave aboard Nossa Senhora da Atalaia severed the surf-line from the cathead. Without this line to steady the boat the overcrowded vessel broached in the breakers, spilling out many who were onboard of whom 50 drowned (Theal, 1902: 305). The survivors dragged the shattered boat to shore but could not save any of its cargo (Theal, 1902: 305-306).

The captain had the boat repaired the next day and offered a reward of 500 xerafins to anyone willing to go back to Nossa Senhora da Atalaia. Nobody onshore accepted the challenge, as the sea was still raging and they were still gripped in fear from the events of the previous day. Those still aboard the ship fired a gun signifying their peril and their cries for help could be heard on shore (Theal, 1902: 306). By this time only the ship’s sterncastle remained above water. At this time stranded people threw themselves into the sea and clung to floating pieces of the hull. Some made it safely to shore while others drowned. The following night some of the African slaves had made their way to shore and alerted the officers that some people remained upon the ship, clinging to a poop-deck rail. At daybreak on July 6th the ship went to pieces, scattering ship timbers across the bay and casting the remains of a few chests upon the shore. The wealthy Portuguese merchants and nobles who sailed upon Nossa Senhora da Atalaia now found themselves poverty-stricken and naked (Theal, 1902: 306).

The captain now assembled the survivors, dividing them into three separate units, taking charge of the passengers, and placing the crew and ship boys under the officers. He designated a few trusted men to gather provisions and had the survivors relocate inland from the beach. Here they made a shelter out of canvas tents, placed the provisions under watch, and planned their future journey toward Cape Correntes. They remained here for eleven days, suffering from starvation and dehydration, as the provisions were minuscule and the water which they gathered from the Infante River was nearly a league away (Theal, 1902: 306). These conditions caused mass illness and several deaths amongst the survivors (Theal, 1902: 306-307). The camp was saved from complete famine by the mussels exposed on the beach during low tide.

The captain entrusted several capable men with the authority to command the survivors, while also designating three men who had previously shipwrecked on this coast as ambassadors should natives appear. On July 8th the pilot and others traveled to the Infante River, from here they could see a thickly wooded ridge lying to the north-west and the shore continuing for over two leagues, which was surrounded by hills of white sand. Here the group measured their latitude as 33 and 1/3°. Natives were spotted on the shore and subsequently approached the Portuguese, but the two groups had no shared language between them.

Back at the camp, the survivors salvaged provisions and supplies were divided and recorded into the king’s book. These included small arms, shot, powder, coconuts, copper for bartering, and lines and hooks for crossing the river (Theal, 1902: 307). Leftover copper and gunpowder was buried in the camp to ensure that the natives did not recover them and possibly inflate their prices when the Portuguese needed to negotiate with them. While sorting through the provisions the Portuguese also discovered that the rice had rotted from the seawater, meaning they would have to expedite their departure. In the days leading up to the departure, the captain tried to persuade the pilot to construct a boat and sail the grievously wounded back to safety, but the pilot refused. One nobleman, who was too injured and sick to walk promised each ship boys 800 xerafins (currency) if they would carry him with a net during their upcoming journey; several other noblemen attempted similar feats, crafting hammocks from nets, rugs, cloth, and oar poles so their slaves could carry them. Others would use bits of wood as makeshift crutches and walking canes, while the healthy carried the arms and bags full of copper and linen (Theal, 1902: 308).

The survivors preferred to delay their departure to heal from the traumas they endured but, the lack of provisions forced them to set out towards Mozambique on July 15th (Theal, 1902: 308). They soon realized that many were too weak to endure the journey, indeed some fell behind on the first day of the trek and were either died from exhaustion and wounds or were killed by natives who trailed the group and looted from any stragglers. After this tragic first day of the journey, a council was held over what should be done about the women and injured. They were already running low on food, had very few goods to offer in barter, and were a month away from any land where they could trade. The council concluded to leave behind those who were unfit to keep pace and that women should march in front, but be abandoned if they fell behind (Theal, 1902: 309). When the Portuguese women were told of this decision they prayed for mercy as they could not accomplish such a task, and consequently, they were left behind without any food to sustain themselves (Theal, 1902: 310).

Months later, towards the end of November, the few who remained of Nossa Senhora da Atalaia’s company met men from the Santissimo Sacramento, their flagship. This vessel had wrecked after their separation and now all that was left of her passengers were nine unarmed men, five of whom were Portuguese, who now joined the Nossa Senhora da Atalaia survivors’ company (Theal, 1902: 349). The following night the nine survivors from Santissimo Sacramento gave the following account of what happened to the Santissimo Sacramento:

During the storm that separated Santissimo Sacramento and Nossa Senhora da Atalaia, the former found herself without a mainsail, but luckily enough to have furled their topsail before the storm. Using the storm sails they steered the ship east-north-east while the storm caused the ship to spring leaks. When the storm subsided the next morning, they were able to stop the leaks but now found themselves without the company of Nossa Senhora da Atalaia. At this time the crew decided to head towards land. They were soon overtaken by another storm. After withstanding this second storm, the Portuguese decided to continue on their course towards the Cape of Good Hope, making sure to stay within sight of land as they did so. On the evening of June 29th disaster struck, as the Portuguese were sailing extremely close to land using the foresail, upon which the chief pilot was directed to turn the vessel out towards the sea, which he did (Theal, 1902: 350). However, after nightfall the chief pilot shifted the course back towards land, whereupon hearing cries from the crew that they were too close to shore he attempted to turn back to sea (Theal, 1902: 350-351).

It was too late. The galleon missed stays, and refused to turn completely, despite efforts to unfurl the foretopsail and sprit-sail. The ship’s bow then turned sharply towards the shoreline, and even with the crew managing the sails and the rudder, she drifted towards land for the next two hours. Eventually, at 34° latitude, Santissimo Sacramento hit a substantial wave that sent the ship to pieces. Previously, many on board, including the captain and the religious, adjourned to the galleries to pray. This act would prove disastrous as the galleries were carried to the depths along with the stern section of the ship upon impact with the wave. Some of the survivors who found themselves on the bow of the ship were able to get ashore by clinging to the yards and pieces of floating timber. A total of 72 individuals survived the wrecking of Santissimo Sacramento and reached shore, many of whom had grievous injuries. The survivors stayed in this spot for eleven days before marching on. After walking for approximately one month, they came across the remains of Nossa Senhora da Atalaia, and a few abandoned stragglers, barely gripping to life, who revealed that they were left behind by the survivors of Nossa Senhora da Atalaia 28 days ago. After retrieving some powder and ammunition from this site, and replenishing themselves with bits of leather, the Santissimo Sacramento compliment marched onward, following a trail of forsaken and or dead from Nossa Senhora da Atalaia’s shipwreck. The Santissimo Sacramento group continued until they reached the river where Nossa Senhora de Belém had wrecked. By this time only 10 of the original 72 Santissimo Sacramento survivors remained, the others had either been left behind, or perished at the hands of the locals, or died from starvation. Many had been left behind when they became too exhausted to continue the journey (Theal, 1902: 351).

The situation deteriorated to the point where Santissimo Sacramento survivors devoured anything which they thought could be edible, from a locust to shoe leather to a mariners chart. Those who consumed the map died of mercury poisoning from its pigments. Eventually, using information given by friendly native people, the Santissimo Sacramento survivors reached their colleagues from Nossa Senhora da Atalaia (Theal, 1902: 352).

The newly constituted group resumed their journey up the coast. By December 14th, the survivors reached the territory of a friendly King Unyaca, who sheltered them and told them of a ship from Mozambique that was anchored at nearby Shefina Island, twelve leagues (about 66 km) away. Several of the Portuguese survivors, escorted by natives, made their way to Shefina, to contact this ship (Theal, 1902: 354). They found a galliot and were happily received by its crew. Upon hearing the survivors’ stories, the captain sent his pilot and a party back to Unyaca, with supplies for bartering. On December 28th the remaining survivors left Unyaca for the Portuguese ship at Shefina, although not all survived this last leg of the journey (Theal, 1902: 355). By January 5th the survivors reached the island where the galliot was anchored (Theal, 1902: 357). They stayed on the island for six months while the ship completed its business, sheltered in straw huts constructed and purchased from the locals (Theal, 1902: 358). While the survivors may have been better sheltered and supplied than they had been previously, more of the Santissimo Sacramento and Nossa Senhora da Atalaia perished. Eventually, the galliot weighed anchor and headed for Mozambique on June 22nd, which they reached on July 9th. From Mozambique, a handful of Portuguese survivors then set out for Goa on September 11th, which was reached on November 8th (Theal, 1902: 359).

Discovery and Retrieval

According to information provided to the Port Elizabeth Museum by C. R. Boxer, Santissimo Sacramento was built of teak in the shipyards of Bassein, north of Goa. It was categorized as an 80-gun galleon. Dutch intelligence reports say it was taken from Bassein to the Peneum River, south of Goa, in April of 1640, a few days before a Dutch fleet blockade of Portuguese ports along the Malabar coast. These Dutch reports also mentioned that Santissimo Sacramento suffered from leaking, had a list, was inadequately furnished, and they were uncertain of her seaworthiness. It was on her maiden voyage to Portugal that Santissimo Sacramento sailed with Nossa Senhora da Atalaia and was subsequently wrecked (Bell-Cross, 1988: 78). Santissimo Sacramento wrecked south-west of modern Port Elizabeth, South Africa, nine miles (14 km) east of the lighthouse at Cape Recife (Allen and Allen, 1978: 39). The area is described as having:

vicious currents swirling in and out among the reefs which lie just offshore, and a succession of small, shallow bays which build up from Cape Recife to Shoenmakerskop (another nearby town) into cliffs falling perhaps a hundred feet to the jagged rocks below… The coastline consists of high rocks inshore with many gullies running between them, with long reefs stretching in places yards out to sea. In some spots there are more reefs even farther out. (Allen and Allen, 1978: 39)

By 1976, David Allen, who grew up in the Port Elizabeth area, was determined to find the wreck of Santissimo Sacramento. Studying historical texts for the possible location of the wreck, Allen soon realized that almost every author on the subject had placed Santissimo Sacramento’s loss at a different spot. The one constant in these discussions, noted by Allen, was the conclusion that Santissimo Sacramento ended up near Nossa Senhora da Atalaia. Allen, however, disagreed with this idea as it did not make sense for the Santissimo Sacramento survivors to march for a month before meeting up with the survivors of Nossa Senhora da Atalaia, as recorded in the shipwrecking account. As well, in Feyo’s account, the larger Santissimo Sacramento was swept out to sea, away from Nossa Senhora da Atalaia. Allen deduced that this meant that Santissimo Sacramento entered the notorious Algoa Bay near Cape Recife, but not too close as Feyo’s account did not include a depiction of the rocks intrinsic to Cape Recife’s landscape. Thus, Allen’s theory favored the one proposed by Eric Axelson in which he claimed that Santissimo Sacramento wrecked at Cape Recife (Allen and Allen, 1978: 45 -46). Allen’s attention was drawn to a 1778 map of Cape Recife drawn by Colonel Robert Jacob Gordon of the Dutch East India Company (Allen and Allen, 1978: 45; Bell-Cross, 1988: 79). On this map, Gordon had precisely illustrated the location of Cape Recife and to the south-east, where modern-day Schoenmakerskop was located, he had added on ‘X’. In his margin notes he annotated the ‘X’ with the following description:

Near the wreck, in the dunes, the remaining miserable castaways had built some shack shelters in the sand, now without… habitants as everybody thinks they died of hunger. I found some skeletons which with the help of my [slave?] I buried. Here the remains of a beautifully carved little box chest of ivory were laying around, which might have been a shrine for a Roman Catholic chalice; also two rusty anchors and a cannon, which as the breakers were strong, the beach rocky, I could not recognize, also some pieces of ebony. (Forbes, 1949: 12, as cited in Bell-Cross, 1988: 79; Allen and Allen, 1978: 45)

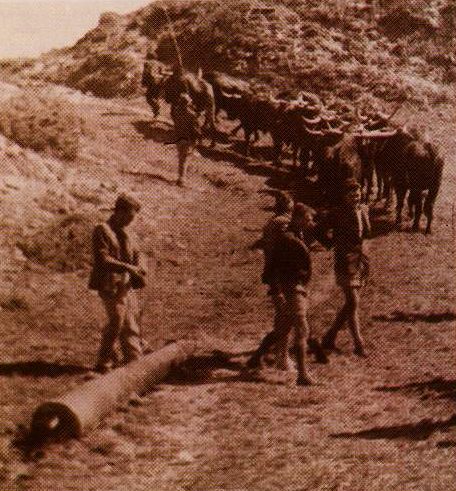

Not long after, Allen came across documents by Mr. H.G. “Hal” Harraway, noted finding a cannon stuck in the rocks near Schoenmakerskop in 1951. Using local laborers and a team of 20 oxen Harraway was able to recover the cannon, which was subsequently put on display in the Port Elizabeth Museum (Allen and Allen, 1978: 46; Bell-Cross, 1988: 79). Harraway detailed the cannon as being made of bronze, weighing up to 6,000 pounds (2722 kg), measuring twelve feet (4 m) in length, and containing an inscription on the barrel that was presumed to have been in Dutch. According to Allen, Harraway contacted the director of the Netherlands Historical Maritime Museum in September of 1960, in part to identify the cannon. In correspondence discovered by Allen, written to the museum by Harraway, he mentioned: “According to the experts who have tried to decipher it the inscription (cannon) should read, ‘Contraet Wegt Woert me Fecit Hagae.’” Thus, Harraway believed the wreck to be Dutch. Allen, unconvinced that the cannon belonged to a Dutch ship, delved further into Harraway’s notes, where he found a reply dated four years later from the Netherlands Historical Maritime Museum that read: “The inscription on the bronze gun should be ‘Conraet Wegewaert me Fecit Hagae’. It is the name of a gun founder working at the Hague during the middle of the 17th century until 1664” (Allen and Allen, 1978: 46).

Allen figured this meant that Harraway’s gun could have been a captured Dutch cannon mounted on Santissimo Sacramento (Allen and Allen, 1978: 46). Harraway reached out to South African geographer Vernon S. Forbes, in an attempt to identify the gun and was told that it probably belonged to a French or Portuguese ship on its homeward voyage (Bell-Cross, 1988: 79). On January 29th, 1977 Allen and his diving partner Gerry Van Niekerk dived at Gordon’s wreck site. Not long into their dive, the pair came across a group of bronze cannons in about 15 feet (about 5 m) of water (fig 31). Recalling the initial discovery, Allen states that the closest cannon was in about eight feet of water, and following a straight line out to sea the furthest cannon was approximately a quarter-mile out. On the first day, the pair recorded up to 21 cannons (Allen and Allen, 1978: 48). After photographing the cannons the following day the pair was wading in knee-deep water when they tripped over the anchor recorded by Jacob Gordon and soon after found bits of ebony nearby. Later the pair learned from locals that occasionally traces of a campsite were present in the area with a trail of white stones leading to the beach (Allen and Allen, 1978: 49). By March 22nd the first of the cannons were raised with a fishing trawler, aided by a team of workers sworn to secrecy and funded by two financial backers (Allen and Allen, 1978: 57-58). The third gun to be raised from the ocean floor was in excellent condition and provided further evidence that the cannons were most likely from Santissimo Sacramento. Visible on the barrel was the Portuguese Crest and the founder’s mark of Portuguese cannon founder A.G. Feyo. The gun had a fuse in its touchhole and was later discovered to be loaded. In all, five cannons were raised on this first retrieval operation (Allen and Allen, 1978: 59). By March 28th the trawler was able to raise seven more cannons. It was in this lot that the largest of the cannons was raised, measuring seventeen feet (5 m) in length (Allen and Allen, 1978: 63).

On April 18th, while attempting to retrieve an additional cannon close to shore, Allen stumbled upon another 30 cannons half a mile (0.8 km) offshore sea. The guns were organized muzzle to breach, as they were stored in the hold of Santissimo Sacramento. Soon after, nearer to shore in approximately 50 feet (15 m) of water, Allen discovered an additional six guns. Upon further inspection, Allen found remnants of the ship’s teak planking under a cannon, as well as portions of ebony and well-preserved peppercorns around and inside the barrels of cannons (Allen and Allen, 1978: 64-65). As the crew began to raise some of these newly discovered cannons it became apparent that sixteen of them were of iron, these were left on the seabed to avoid rapid corrosion in the air. By April 24th, six more cannons had been retrieved. The following day the team recovered the best-preserved cannon thus far, containing an intricate scroll mark and lotus bud decorative reliefs on the cascabel, this cannon would later be identified as a Bocarro cannon. Underneath the gun additional pieces of wood were discovered, later identified as Indian teak by government laboratories in Pretoria (Allen, 1978:67). By the end of the day, the team retrieved a total of 21 guns from the site (Allen and Allen, 1978: 68). Towards the end of April Allen discovered the detached cascabel of a cannon in the form of a clenched fist with a pointed thumb penetrating out from under the index finger, later confirmed as a fertility symbol found on Bocarro cannons. Nearby was a fully intact cannon with a matching cascabel. This cannon would be later referred to as the Bocarro “miracle cannon” (fig 32) (Allen and Allen, 1978: 68, 72). With the addition of this cannon, Allen’s team had now discovered a total of 41 cannons at the wreck site. Authentication of their Santissimo Sacramento provenience was confirmed by an inscription on the most well-preserved cannon which read: “Antonio Teles Menezes, Governor of India, ordered this in the year 1640 by Manuel Taveres Bocarro” (Allen and Allen, 1978: 69).

In addition to this inscription, contemporary Dutch reports were made available by C. R. Boxer which claimed that Santissimo Sacramento sailed from Goa in 1647, “Fully laden with the most beautiful goods… and in her hold came a quantity of cannon which the City of God (Macao) in China sent as a present to his majesty” (Allen and Allen, 1978: 69). By April 29th, an additional small bronze cannon was raised from the site and on May 2nd, the crew retrieved the so-called miracle cannon. Afterward, the crew raised the remaining cannons from the area of the supposed hold, five in total that day, and recorded the locations of the iron cannons still resting on the seafloor. On May 11th, seven more bronze cannons were raised from the seabed (Allen and Allen, 1978: 70). The crew returned to the wreck site on the May 20th, retrieving six bronze cannons, one-half of a gun, and a roll of lead believed to have been used for ship repairs onboard Santissimo Sacramento. This last trip finalized the salvaging of the wreck site (Allen and Allen, 1978: 76). By the end of the project, a total of 40 cannons were retrieved from the wreck of Santissimo Sacramento, 21 of which were believed to have been originally stowed in the ship’s hold (Table 5). Unfortunately, by July 8th, 17 of the more degraded bronze cannons were sold for scrap at 75 cents per kilogram (Allen and Allen, 1978: 76).

Aside from the ebony and teak previously mentioned by Allen, other recovered artifacts included blue-and-white porcelain and stones of granite porphyry that could have belonged to the ship’s ballast (Bell-Cross, 1988: 79).

Due to Santissimo Sacramento’s archaeological inventory consisting almost exclusively of bronze cannons it is vital to know how such guns were made and used to fully understand their context aboard the Santissimo Sacramento and broader significance to 17th century naval artillery. I turned to a publication by John F. Guilmartin, Jr. titled “The Guns of the Santissimo Sacramento”, not to be confused with the publication by Geoffrey Allen and David Allen titled “The guns of Sacramento”, The Guilmartin study evaluates guns from the Portuguese 60-gun galleon that wrecked in Brazil in May 1668, while Allen’s work details the 80-gun Portuguese galleon that wrecked off the coast of south-east Africa in 1647 (Navegantes, 1979: 215, as cited in Guilmartin, 1983: 559, 570; Allen and Allen, 1978).

The first point to be discussed on the topic of 16th to 17th century muzzle-loading, black-powder cannons, is that the potential maximum velocity is reached at around eighteen calibers down the barrel or eighteen times the bore diameter. Black powder’s burn rate does not change due to pressure or temperature, meaning the effective barrel length is essentially static and any additional barrel length over eighteen calibers does not affect the cannon’s range (Guilmartin, 1974: 277-283, as cited in Guilmartin, 1983: 563). Guilmartin states that smoothbore cannons using spherical projectiles were essentially inaccurate; the shot bounces randomly down the length of the bore, thus acquiring spin, rendering any attempt to hit a target over 500 yards (472 m) fruitless. Furthermore, an iron cannonball has finite destructive power towards the end of its range, aside from when a lucky shot may hit a spar or slice a piece of rigging (Guilmartin, 1983: 565).

Guilmartin goes on to point out that barrel lengths for bronze cannons were integral to the strength of the gun. In western European tradition, cannons were cast in a pit breech down, with the molten bronze poured into the mold at the muzzle through a casting bell (Guilmartin, 1974: 284-291, as cited in Guilmartin, 1983: 564). Because the pressure of the molten metal was proportionate to the height of the liquid column, the casting bell lengthened the height of the column, increasing the pressure under which the bronze at the breech solidified. The bell was removed after the casting. This technique increased casting pressure, aided in reducing the negative effects caused by impurities in the metal, and given the inherent porosity of bronze, made it stronger towards the breech where the powder ignition occurred (Guilmartin, 1983: 564). Furthermore, the thicker the barrel, the stronger the cannons tended to be. As founders became more skillful, namely able to maintain a better quality of metal, cannons shrank and thinned (Guilmartin, 1974: 170-173, as cited in Guilmartin, 1983: 564-565).

According to Guilmartin, knowledge of the principles of gun founding was represented in works of superior founders who were also consistent in weight, dimensions, and metal composition. Such skill and knowledge helped in reducing the amount of bronze used in the casting process, resulting in lighter, more cost-efficient guns, and superior pieces. Casting a cannon with inadequate strength could have disastrous consequences, causing it to burst when firing. Guilmartin noted that bore length and barrel-wall thickness as functions of bore diameter give a good indication of the quality of the cannon (Guilmartin, 1983: 566).

As for the relationship between cast iron and bronze cannons, the former were heavier and larger even though they were designed to fire identical projectiles. Cast iron cannons were also subjected to greater levels of corrosion and were generally less safe when bursting, as they tended to not remain intact as bronze cannons did. While the latter type would rupture “like a torn sponge along a longitudinal line near the breech”, iron cannons “blew apart in jagged fragments like a bomb” (Guilmartin, 1983: 567). Despite their dangerous qualities iron cannons were used widely because iron cost about a third of the price of bronze. Iron guns were not considered the weapon of choice during this period (Cipolla, 1965: 45, as cited in Guilmartin, 1983: 567). Following the restoration of Portugal’s independence from Spain, in 1640, the country had a shortage of quality cannons, indicated by Portuguese dependence on Swedish cast-iron ordinance (Cipolla, 1965: 56, as cited in Guilmartin, 1983: 574).

Guilmartin suggests that the shift from stone shot-throwing cannons and those designed to throw iron projectiles during this era can be explained as a matter of cost-efficiency. The crossover from stone to cast-iron cannonballs was a symptom of rising labor costs in Europe, especially in Northern Europe. While stone firing cannons required a third less bronze than cannons firing cast iron the labor cost for stonecutters was immense (Guilmartin, 1983: 590). As wage rates rose at the beginning of the 16th through the 17th century, the use of stone-throwing cannons fell out of practice, especially in northern Europe (Slicher Van Bath, 1963: 113-115, as cited in Guilmartin, 1983: 590). However, where labor cost was lower stone-throwing cannons continued to be cast, and the Portuguese continued to cast them in India through the middle of the 17th century, long after the Europe-based gun founders had stopped doing so (Guilmartin, 1983: 591).

In his analyses of the guns from the 1668 wreck in Brazil, Guilmartin notes that the collection of bronze guns recovered from the lower gundeck included a 28 pounder cannon cast by A.G. Feyo, the same founder who cast at least one of the cannons from the 1647 wreck (Guilmartin, 1983: 575; Allen and Allen 1978: 59). Another gun on the 1668 wreck, an 11 pounder from the upper gundeck also contains the founder mark of A. G. Feyo (Guilmartin, 1983: 584). Lastly, a Dutch 20 pounder found on the 1668 site, cast in 1649, contains the founder mark of Conrad Wagwaert, the same Dutch founder who cast the Dutch cannon recovered by Harraway (Table 6) (Guilmartin, 1983: 592; Allen and Allen 1978: 46).

Ballast

I

Anchors

N

Guns

N

Iron Concretions

N

Hull remains

T

Caulking

Not reported.

Fasteners

A

Size and scantlings

T

Wood

No timbers were reported

Reconstruction

Beam: Estimated m

Keel Length: Estimated m

Length Overall: Estimated m

Number of Masts: Unknown

References

Allen, Geoffrey e Allen, David – The Guns of Sacramento, Ed. Robin Garton, London, 1978.

Axelson, Eric, “Recent Identifications of Portuguese Wrecks in the South African Coast, especially of the São Gonçalo (1630), and the Sacramento and Atalaia (1647),” typed manuscript in Estudos de História e Cartografia Antiga, Memórias, nº. 25. Lisboa: Instituto de Investigação Científica e Tropical, 1985.

Boxer, C.R., A Índia Portuguesa em Meados do Séc. XVII. Lisbon: Edições 70, 1982.

Paez, Simão Ferreira, As famosas Armadas Portuguesas 1496-1650. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Marinha, 1937.