Identity is a central in archaeology. Archaeologists associate the concept of identity with human beings as it refers to age, gender, ethnicity, religion and status. It can either describes individual or group identity and one can have more than one.

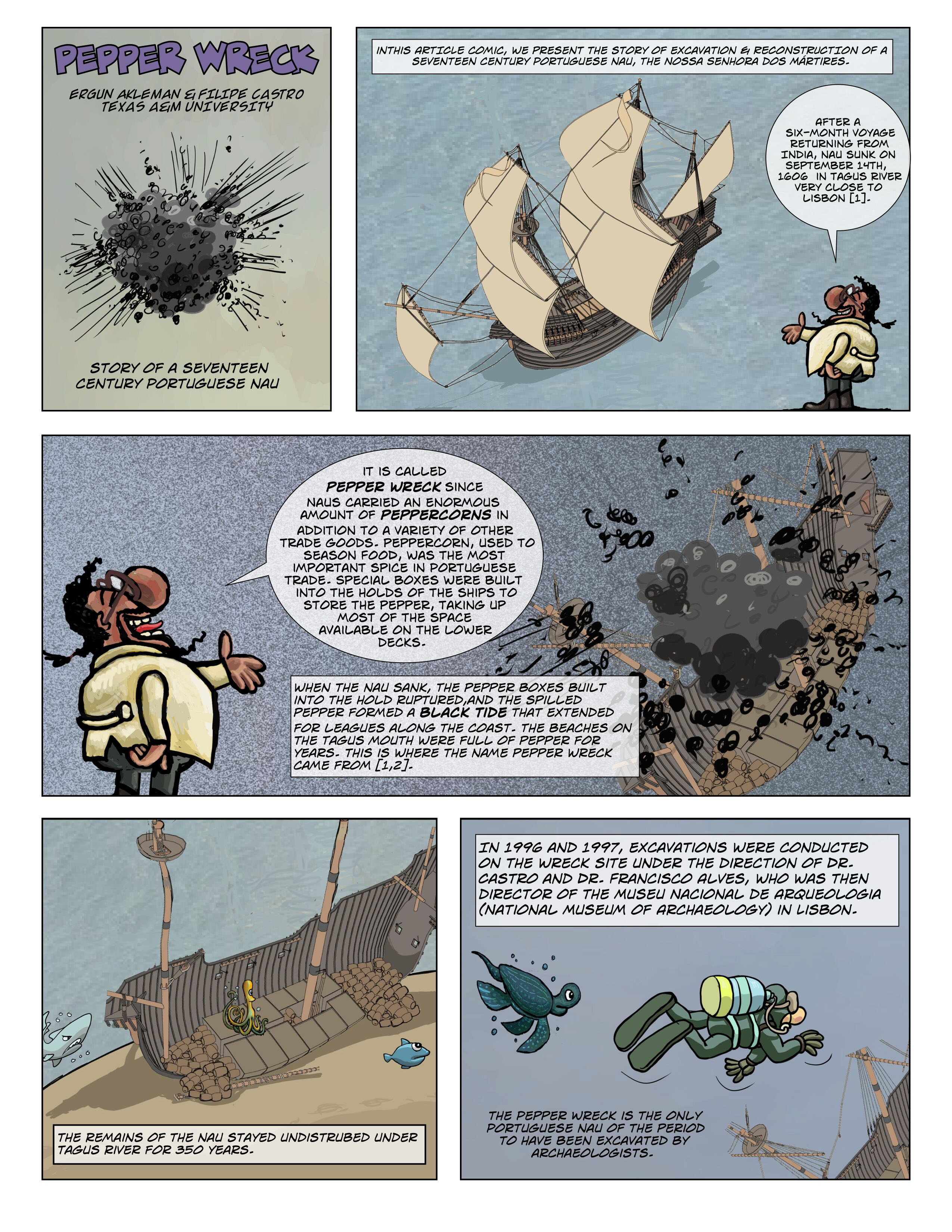

A first definition for identity could refer to the humans on board. The use of material culture to determine the ethnicity of those aboard the vessel is common in the study of shipwrecks, especially for the antique ones as artefacts are often the only remains left. The identification of cargo and daily life artifacts can lead to the identification of trade networks but also to the ethnic identification of some people on board.

However, studies on onboard people identity do not always match the nationality of a ship itself. People were mobile, and their presence on board only reflects only a small period of time in the ship’s history, often the last trip. Crews were often multi-ethnic, and do not necessarily reflect the nationality of the ship. The same problem is encountered with the cargo. The origins of the artifact found on a wreck can improve our understanding of trade networks, but they can be independent from the ship itself.

Regarding the ship itself, the flag or ownership under which the ship once sailed could be seen as a good way to identify the nationality of the ship, but only when historical records are available. One should, however, keep in mind that ships could be bought from another country or that ships can be captured and sail under new ownership.

The location of the shipyard can be a good indication of a ship’s nationality, but it is not always available through historical records. Moreover, knowing where the ship was built does not always indicate who built the ship, and it cannot exclude the potential presence of foreign shipwrights building who might have constructed it on commission. Through analysis of the wood, it is also possible to pinpoint a general origin from the timbers used but again, timbers traveled across territories.

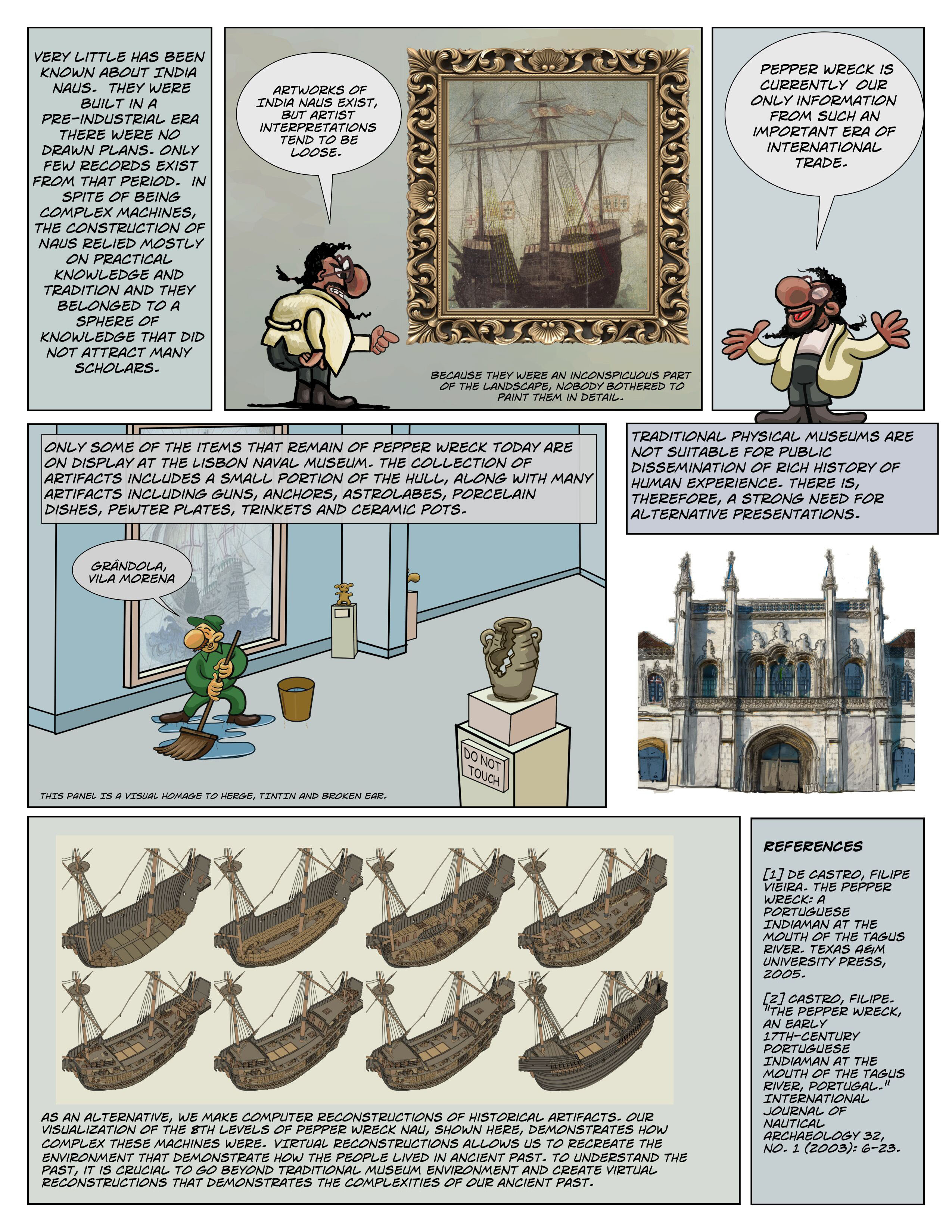

Finally, the shipwreck itself can have its identity associated with its architectural features. For example, studies led on ship build in the Iberian Peninsula during the 15-16th century show that they share similar construction features. Other shipbuilding traditions can share common features or common measurement system that can provide archaeologists with some indications of the ship’s origins.

***

Whether it is the association of the ship to a specific type, function, region, tradition or, in some case, its name and country of origin, these associations are important for the discipline of nautical archaeology. The possibilities are numerous, and they all reflect different levels of the identity in a ship. It is part of the archaeologist role to understand their ship identity through all the evidence found on the shipwreck site!